|Penny Folger|

Bram Stoker’s Dracula plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, October 20th, through Sunday, October 22nd. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a novel that was originally published in 1897, was later adapted to film over 200 times. What led Francis Ford Coppola to make it again in 1992, on the heels of his Godfather III?

The answer can be found in then 19-year-old Winona Ryder.

After dropping out of Godfather III due to nervous exhaustion (and being replaced by Sofia Coppola who was famously maligned for her performance), Ryder met with the senior Coppola to make amends and brought him the Dracula script. The idea struck a chord with Coppola, who, as a teenage drama camp counselor, read Bram Stoker’s novel to his young campers every night.

Coppola was interested in making a film that was more faithful to the novel than the myriad of previous film versions had been. As he explained, “There were so many of them, but no one ever did the book!”1 Yet the crux of his film: the love story between Dracula and Mina Murray—the woman who mysteriously resembles his late wife from another century—is not one that appears in Stoker’s novel at all.

In terms of Universal’s classic monster movies, Coppola’s Dracula does not resemble Dracula with Bela Lugosi so much as it does The Mummy starring Boris Karloff (interestingly, Coppola thought about remaking Frankenstein as well, but wound up only producing it). In The Mummy, directed by Karl Freund and released in 1932, Karloff’s monster also believes a contemporary woman is the reincarnation of his lost love. As Gary Oldman as Coppola’s Dracula puts it, “I’ve crossed oceans of time to find you.”

Why did Coppola change this major plot line if he was trying to make a faithful adaptation? Roger Corman, who mentored not only Coppola but directors such as Martin Scorsese, Ron Howard, and James Cameron (to name a few) once told a mentee, director Amy Holden Jones, that a movie needed to contain either sex, violence, or humor in order to succeed.2 A few steamy love scenes between Ryder and Oldman (who reportedly did not get along during filming) involving blood and lust seem influenced by this school of thought, yet Coppola attributes the screenplay entirely to screenwriter James V. Hart. So it’s not clear, with his improvisational rehearsal style and encouraged input from the cast, how much of this Coppola may have influenced.

Another element of the Corman philosophy of filmmaking employed here: the sexualization of Lucy’s character. The novel continually emphasizes how “sweet” and “pure” she is, which provides greater contrast once Dracula corrupts her: “the blood stained, voluptuous mouth, which made one shudder to see, the whole carnal and unspirited appearance, seeming like a devilish mockery of Lucy’s sweet purity.”3 In the novel, she is changed from “purity to voluptuous wantonness” once evil hits.4 Despite having three suitors, she’s not sexually voracious and “naughty” even before Dracula arrives, as Sadie Frost portrays her under Coppola’s direction. She doesn’t do orgasmic writhing in scantily clad red nighties either: if she does, it’s during one of her “blackouts” not elaborated upon by Bram Stoker. This purity vs. sexual liberation (at one point she even shares a playful kiss with Mina) feels a lot like the difference between a 19th Century notion of womanhood vs. one from the 1990s.

“I didn’t think my job was to come in here and do the same thing over again,” explained Coppola when addressing his take on the material. “I took the path that was really out of my heritage and my background and my training and my view of things.”5

In service to this, Coppola led a kind of “summer camp” at his own estate prior to filming, largely to ensure they had rehearsal time, where (much like with his former campers) he made the cast read the entirety of the novel aloud over a three day period. This was partly to ensure they had all read the book, but also so they could tell him if they felt anything crucial was missing in the adaptation. As a result, everyone tried to make their parts bigger.

Every frame of Coppola’s Dracula was painstakingly rendered and shot almost entirely on soundstages at the former MGM studios. Coppola, who grew up terrified of Bela Lugosi’s Dracula even when he appeared alongside comedy duo Abbott and Costello, decided against shooting on location. Coppola imagined, “I’m going to be there in the middle of the castle where Dracula actually was and it’s going to be two in the morning and I’m going to be alone in the room trying to work out the shot and god help me, Dracula’s going to come and get me.”6

Playing into a reputation for overspending that plagued him since Apocalypse Now, Coppola told the studio he would shoot entirely in a soundstage right under the studio’s noses rather than flying off to Romania—a pricier endeavor where they would have less control over him. They took his bait.

“I really loved the way this film was shot with everything looking really like an old movie,” said Ryder. “You wouldn’t have been able to get that if you’d used the real castles and real locations.”7

The unique analog look the film has can be attributed to Coppola’s ideas behind its effects as well.

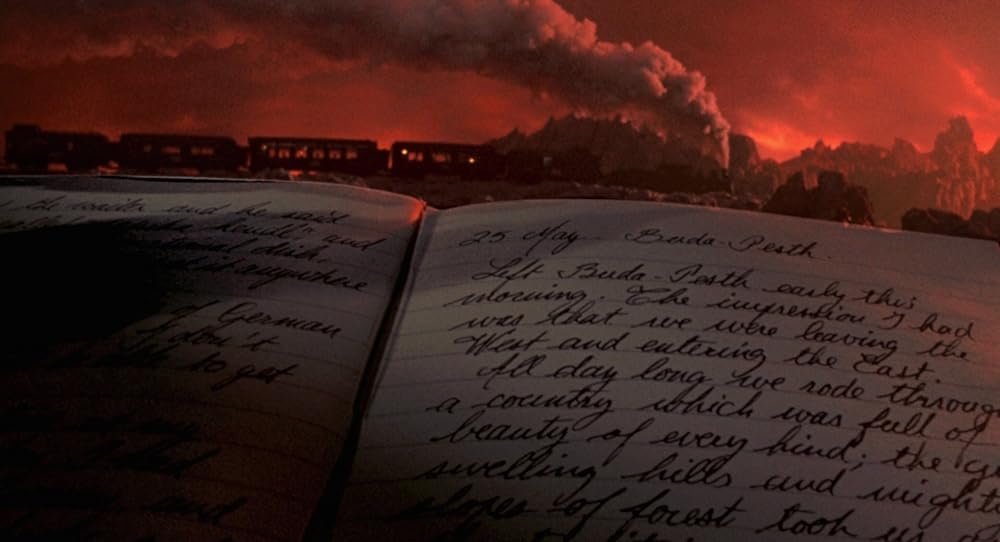

Coppola found it significant that the novel was written in the same era as the birth of cinema and used that to make a key stylistic choice. “I thought that I would not only make the film entirely in a false place (in a studio) but I would only use effects done as they would have been done in 1900.”8 He utilized vintage special effect techniques “where you actually make the effect live on the stage and not do it later in post.”9 It’s an ingenious idea that gives the film a special and unique visual feel, but it was maddening to crew members accustomed to working in the modern era.

Coppola’s head of special effects balked at the idea of using only live effects or multiple exposures and said this was not only, “just not done anymore,” but “wasteful and absurd.”10 He quit soon after, and Coppola brought in his 27-year-old son Roman to replace him, who was fascinated with the idea of in-camera effects and a lifelong student of magic. Coppola suspected he could only really trust his immediate family to carry out his unorthodox vision the way he wanted it. “I began to realize that it was only my own family who… would be there shoulder to shoulder with me, pushing it to be what I hoped it could be.”11 Commented Roman on the period effects they employed, which mirrored directors like Georges Méliès and the birth of cinema: “We pretty much used every trick in the book.”12

Coppola also fired his original production designer, who tried to rebel against his minimalist ideas about the film’s sets. Coppola had the idea that the costumes would take center stage against minimalist sets with wide open spaces fading into darkness. According to the film’s costume designer Eiko Ishioka, who won an Academy Award for her efforts, Coppola said, “Eiko, for Dracula, costumes will be sets” and “sets are going to be lighting.”13

Johnny Depp, Winona Ryder’s partner at the time, was supposed to play Jonathan Harker but the studio objected to his casting at the last minute because he wasn’t a big enough star at the time. Ryder and Depp, surprised at Coppola’s lack of absolute power over the studio, expressed their disappointment by saying, “But we thought you were God.”14

Keanu Reeves, a friend of Ryder’s, won the role instead—the two were said to have been married on the set because the wedding ceremony in the film was performed by a real priest. Reeves was much maligned for his character’s accent after the film’s release. He later said that he was exhausted coming off of multiple projects at the time and didn’t feel he had given the role his best. Coppola defended him. “We knew that it was tough for him to affect an English accent. He tried so hard. That was the problem, actually—he wanted to do it perfectly and in trying to do it perfectly it came off as stilted. I tried to get him to just relax with it and not do it so fastidiously.”15

Anthony Hopkins, on the heels of his Oscar winning performance in Silence of the Lambs, did not like Coppola’s extensive rehearsal process, yet improvised within it: he and Coppola concocted a Van Helsing who was loony and unpredictable. Said Coppola later, ”I wanted him to have a good note of madness in him.”16 This made him more of an energetic match for Oldman’s Dracula, who, at Coppola’s request, would whisper disturbing things into the ears of other cast members as they stood blindfolded in order to escalate their fear before shooting. Oldman and Coppola’s relationship during the production was reportedly rocky. “We never saw eye to eye on certain things,”17 Oldman later admitted.

Pushing his unorthodox film to the finish line—and stubbornly making it his own way, regardless of how many crew members he had to replace—Coppola faced pressure to conform that he found common in Hollywood. “There’s a pressure to do things the way you always do them,” he explains. “You begin to wonder why the movies you go to see sort of all look the same. It’s because the solutions to problems are done a certain way.”18 Yet Coppola was enough of a maverick that he sought alternative solutions that served not only his film, but its contribution to the greater art of cinema. Coppola hoped that his vintage effects would give the film “a mythical soul.”19 It feels like he succeeded. Amidst all the struggles, Coppola’s determination and the new-old innovations he achieved with the help of his family, the film’s sheer beauty stands the test of time, much like Dracula’s love for Mina.

- Aubry, Kim. Director. The Blood is the Life: The Making of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, 2007. ↩︎

- Jones, Amy Holden. “Hail to the King: A Celebration of Roger Corman,” Aero Theatre (September 30, 2023). Santa Monica, California. ↩︎

- Stoker, Bram. Dracula. Duke Classics, 2012 [1897]. ↩︎

- Stoker, Bram. Dracula. ↩︎

- Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Commentary by director Francis Ford Coppola. 2006. ↩︎

- Reflections in Blood: Francis Ford Coppola and Bram Stoker’s Dracula, 2015. Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. ↩︎

- Ryder, Winona. Bram Stoker’s Dracula 1992 – Bobbie Wygant Archives. ↩︎

- Aubry, Kim, Director. In-Camera: The Naive Visual Effects of ‘Bram Stoker’s Dracula.’ 2007. ↩︎

- Practical Magicians: A Collaboration Between Father + Son. 2015. ↩︎

- Reflections in Blood. ↩︎

- Aubry, Kim, In-Camera. ↩︎

- Practical Magicians. ↩︎

- Aubry, Kim, Director. The Costumes are the Sets: The Design of Eiko Ishioka, 2007. ↩︎

- Reflections in Blood. ↩︎

- McGovern, Joe. “Francis Ford Coppola remembers Dracula, firing his VFX crew, and Keanu Reeves’ accent.” Entertainment Weekly (October 6, 2015). ↩︎

- Reflections in Blood. ↩︎

- Aubry, Kim, Director. The Blood is the Life. ↩︎

- Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Commentary by director Francis Ford Coppola. 2006. ↩︎

- Aubry, Kim. In-Camera. ↩︎

Edited by Finn Odum

Insightful article with so many behind the scenes details! It really makes me want to watch this film.

Tremendous article! The time and effort Trylon people put into their movie choices makes me want to donate money. Where else in the Twin Cities can anyone get this kind of value !