|Chris Polley|

Bram Stoker’s Dracula plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, October 20th, through Sunday, October 22nd. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Besides both of us being complete dorks, the venerable, legendary auteur Francis Ford Coppola (of Godfather and Apocalypse Now fame) and I have exactly one thing in common: We both forced a group of people to sit down and read Bram Stoker’s iconic gothic novel Dracula out loud together. Sure, he did it under the auspices of adapting the famous story for the screen with a cast of heavy-hitters, while I did it because I was a brand-new teacher at an alternative high school that didn’t know what else to do to keep troubled teenagers’ attention, and there just so happened to be a giant pile of mass-market paperbacks of the vampire story in my classroom just as the adaptation of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight had hit movie theaters. We did it for similar reasons too—Stoker’s text is potent and like poetry, and so it deserved to be not just read but heard.

“Coppola insisted on the cast understanding Stoker’s novel from start to finish and instead of diluting Stoker’s work he made a conscious decision to include as much as possible,” Graham Connors writes for HeadStuff.1 Thus began the vineyard visionary’s mission: create the definitive retelling of a story known for nearly 100 years by the time 1992 rolled out as one to be retold ad nauseam. “He wanted to close the book on this story and be the quintessential telling of Dracula from Bram Stoker’s perspective,” Cary Elwes (who plays galavanting nobleman-cum-vampire-hunter Arthur Holmwood) told The Digital Fix last year in conjunction with the film’s 4K re-release on its 30th anniversary.2 At this point, Coppola had made the most epic crime story for the big screen and the more surreal and startling depiction of war for it too. This kind of brash, grandiose attempt wasn’t just expected from the director by the 90s, it was downright celebrated.

Of course, between the bold coupling of faithfulness to the source material and the brazen fever dream aesthetic, the romantic excesses and the languid indulgences, Bram Stoker’s Dracula caused a frenzy of reactions from critics (but still more positive upon research and reflection than one would think considering the film’s spotty legacy). Despite this, and arguably more surprising than its wide spectrum of critical reactions, the film was a bonafide hit with general moviegoing audiences, earning Columbia Pictures over $215 million on a $40 million production budget. Lump it in with the two other most well-reputed vampire films of the decade (Stephen Norrington’s campy comic book flick Blade made $131 million, while Neil Jordan’s powerhouse Interview with a Vampire grossed a comparable $223 million — though on a budget of $60 million), and it becomes clear that the 90s were the ideal era for adapting literary bloodsuckers with viciousness and vibrancy.

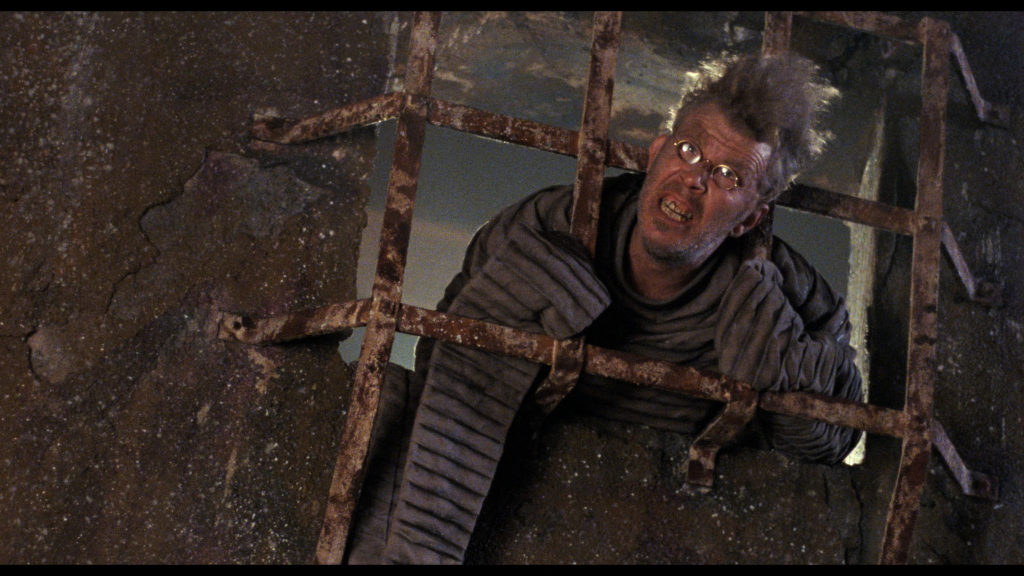

What set Coppola’s masterwork apart from the others in the genre the most, though, regardless of time period, was his approach to visual effects. He set out, unlike nearly every attempt prior (with the exception, perhaps, of F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu) from the start to capture the kind of gothic gonzo imagery in Stoker’s novel. To do this, Coppola famously fired his VFX crew early on and replaced them with his son Roman, who was just 26 years old at the time with only a couple minor credits to his name (though he would go on to collaborate, write, and produce with the likes of Wes Anderson, his sister Sofia, and more). Coppola Sr. described his indulgent yet patient process (that likely was easier to execute with his progeny overseeing it) to Entertainment Weekly in 2015: “You photograph a scene and then you make good notes and you put it in the refrigerator and a week later you take the film out and then put it in the camera, and re-photograph the next element. In some cases we passed the film through the camera three or four times before it was developed. It’s very difficult, but the photography you get is very beautiful.”3 And how beautiful it is—nearly every frame chock full of the awe-inspiring and innovative, hypnotizing the viewer to gaze upon it and relish its twisted grandeur.

Whether it’s a toxic (and intoxicating) green mist floating through a castle silhouette and other silent era double (or even triple, nay, quadruple!) exposure trickery, or the ornate costuming from Eiko Ishioka (who fellow auteur Paul Schrader smartly scouted from the cosmetics commercial industry for his Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters and went on to devise equally spellbinding and singular costumes for Tarsem’s The Cell and The Fall in the 00s), Coppola was obviously happy to go off the deep end of the artform and ascend back up like a certain caped count with daring confidence. Exactly two decades after The Godfather, he re-cemented his prowess for bringing books to life on screen in ways no one else could possibly have imagined. That is, of course, if you don’t mind all the stuff he also made up that wasn’t a part of Stoker’s original text at all.

As Cordula Lemke writes in her book The Medieval Motion Picture, “[Coppola] adapts Stoker’s novel and previous film versions, but he also adapts the Middle Ages for a twentieth-century audience; his adaptation addresses both the history of media and the history of ideas.”4 Just as Coppola did in his past works for the Mekong River and Sicily, but with even more far-reaching research in the fields of history, art, cinema, architecture, and warfare this time, Bram Stoker’s Dracula never fails to impeccably depict distinctly unamerican locales. From the bloody battlefields of the Ottoman Empire to turn-of-the-century London, the filmmaker’s paintbrush (along with frequent Fassbinder and Scorsese collaborator Michael Ballhaus as director of photography) that aimed not only at both pleasing and disturbing the eye, but also provoking the mind and, yes, libido.

At the center of Coppola’s rendition of the classic tale is a frenzied meditation on creation and elimination, not unlike Stoker’s original text and its haunting obsession with the struggle between embracing modernity and returning to tradition. And within these themes, and overlapping all of them, are the brutal violence and sexual overtones that permeate the narrative in ways both alarmingly explicit as well as darkly comical. All of these motifs come to a head in Coppola’s signature scene addition to James Hart’s (Hook, Contact) already dense screenplay: when the titular creature of the night (played with fanged ferocity by Gary Oldman) hypnotizes Mina (Winona Ryder towing the line between voyeur with agency and object of the male gaze) at a nickelodeon screening early works of cinema by the Lumière brothers.

It’s a bit much for those of us knee-deep or more in film history, but the audacity is essential to the spectacle of sensation, and to the wicked humor that brightens the whole steamy, ridiculous affair. Like the best of camp, it’s aware of itself as well as its sordid connections to the wild stories, forms of communication, and artistic expressions of the past. Literary scholar Sigrid Anderson Cordell says, “Coppola’s film, like other neo-Victorian texts, reflects an awareness of the difficulties of knowing the past that resonates with the Victorian emphasis on using technology, and most especially technologies of vision, to make the past objectively knowable.”5 Likewise, Stoker’s epistemological source material does well to consider various methodologies of writing such as achingly raunchy love letters and diary entries full of yearning and sweat, both aware of his doomed characters’ human weaknesses and yet also empathetic to their attempts at understanding and documenting—nay, creating—truth.

In fact, it was this very element of Stoker’s text that made reading it aloud with my students once upon a time so discomfortingly comedic and memorable. I recall one particular day of taking turns with the climactic dictations of Dr. Jack Seward’s phonographic diary, wherein a colorful cast of rogue suitors of Mina’s friend Lucy (now a vampire under Dracula’s power) work with the magnanimous Dr. Abraham Van Helsing to drive a stake through the poor young woman’s undead heart, and behead her for good measure. Stoker’s descriptions of the bloody sequence are so full of passion and innuendos that at one point the student reading had to stop and ask, “Mr. Polley, is this a sex scene?” When I responded with a curt “well, that’s an interesting interpretation,” another student chimed in: “Okay, it’s official. This is better than Twilight.”

- Graham Connors, “Literature On Film | Part 1 | Francis Ford Coppola’s Adaptation Of Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” HeadStuff, October 30, 2015. ↩︎

- Anthony McGlynn, “Cary Elwes: ‘Francis Ford Coppola wanted to close the book on Dracula’,” The Digital Fix, October 5, 2022. ↩︎

- Joe McGovern, “Francis Ford Coppola remembers ‘Dracula,’ firing his VFX crew, and Keanu Reeves’ accent,” Entertainment Weekly, October 6, 2015. ↩︎

- Cordula Lemke, The Medieval Motion Picture (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 42. ↩︎

- Sigrid Anderson Cordell, “Sex, Terror, and Bram Stoker’s Dracula: Coppola’s Reinvention of Film History,” PhD diss., (University of Michigan, 2013). ↩︎

Edited by Finn Odum