| Kevin Maher |

Fearless plays at the Trylon from Friday, September 8th, through Sunday, September 10th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

I was a frequent flyer throughout my career, logging more than 1 million miles on Delta alone. There were many flights that were so turbulent that I remember calculating which would be better: to crash in Lake Michigan, hoping for a ‘miracle on the Hudson’ outcome, or a rougher landing in some field. It was silly, but it passed the time as the plane rocked from side to side or dropped in altitude. Afterward, I would remind myself of the odds against plane crashes and get on the next flight. Peter Weir’s Fearless, however, planted the seed that perhaps activating a calming mechanism in the brain would not change the outcome, but might lead to some kind of an epiphany; a sense of freedom before death.

Screenwriter Raphael Yglesias based his novel of the same name on the United Flight 232 crash in Sioux City, Iowa on July 19, 1989, which killed 112 of the 296 people on board. While the incident was the deadliest plane crash in U.S. history at the time, it was also hailed as an example of exemplary crew management. The crash was dubbed an “impossible landing” because the crew lost control of the hydraulic systems necessary to command every instrument on the plane. Instead of focusing on the heroics of the crew, however, Yglesias told the fictionalized story of some of the incident’s survivors and the impact of grief, guilt, and shame they experienced in the aftermath. Issues with God, love, exploitation, and faith—in their unique extremes—also affect individual characters in this wholly unique and emotional film.

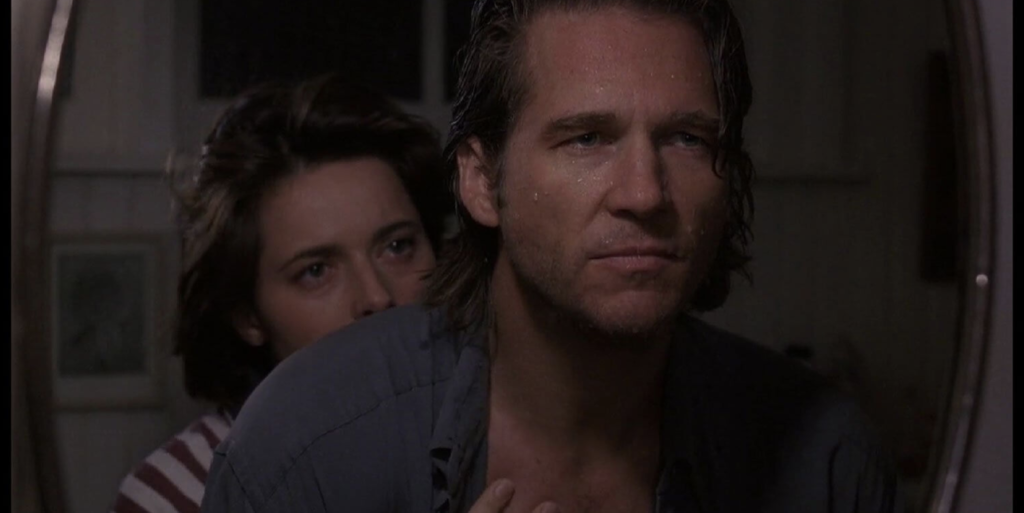

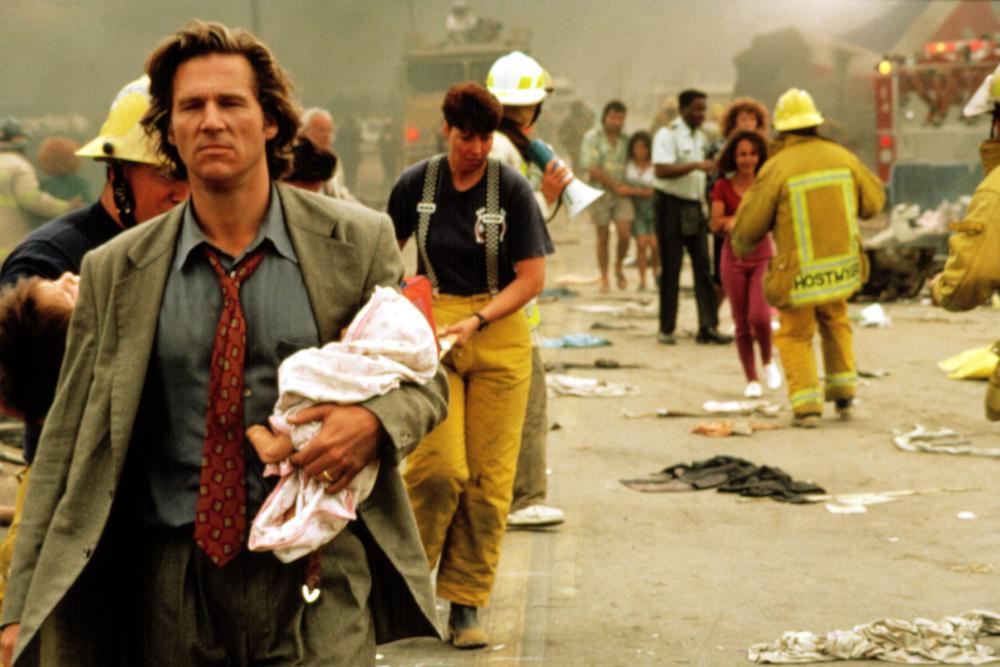

Fearless has been described as having hallucinogenic qualities through its continual shifting of perspective and place, flashing back to the crash at different moments, and opening in a hazy and otherworldly landscape before pulling back to reveal the larger carnage of the crash scene. Jeff Bridges, playing survivor Max Klein and dubbed the good Samaritan for having led a group to safety in the aftermath, moves through his trauma in fits and starts, adding an ephemeral nature to reality. His surprise at the realization of survival quickly gives way to euphoria, then nostalgia and disassociation. At one point he even comforts another survivor, telling her they are ghosts as they move through a crowded mall unnoticed. He floats from interaction to interaction, never engaging deeply and never sharing the depth of his emotional reaction to his survival. In what is considered one of Bridges’ best performances, while Max Klein shares the detached personae of his other characters, there is clearly a deep emotional current here. In a 1993 Movieline Magazine interview, Weir notes that he was ‘photographing souls’ as he captured the surviving characters, and Bridges’ performance directly reflects that idea.1 The viewer sees his body, hears his voice, and watches his movements, but experiences something entirely different; something untouchable.

If Max Klein floats above life, then Rosie Perez’s grieving mother Carla Rodrigo wallows in it. While she survived, her baby died, having been ripped from her arms on impact. She is practically catatonic when a psychologist introduces her to Klein, setting off the emotional core of the film. As the two struggle to understand their emotions, a deep bond begins to develop. Emotionally, Carla swings wildly between self-hatred, overwhelming grief, and despair in the loss of certainty of her faith. Together, they float alone together, free from the ignorance of those who love them and surround them. They become a world unto themselves, able to laugh, to live, and to feel something—if only for fleeting moments. Perez is magical in her performance, complete and demanding attention whenever she’s on screen. The intimate scene she and Bridges share in a car—ending with a tentative kiss—begins their reawakening, allowing the viewer to see that possibility before the characters. It’s a masterclass in performative simplicity.

For both characters, there is an epiphany that brings them back to “life.” For Carla, it is the realization that she cannot be blamed for her child’s death—a realization that is literally smashed into her, but ultimately frees her to live as she knows she must, by starting over. She breaks with Klein, allowing him to begin to do the same. Klein is different, however, as he continues to tempt fate, to tempt God, to take him for good. He is alive, but not living. He is a soul free of commitment and unable to associate with the body he’s trapped in. It takes a simple act—the bite of a strawberry that constricts his throat—for him to see death before finally uttering “I’m alive” to his thankful wife.

Weir and Yglesias deftly define the gap between living and being alive. For Max and Carla, surrounded by reporters, lawyers, psychologists, and loved ones, there is no living without a sense of life. They have experienced death, but they live on, destined to be tortured souls without purpose. Only after recalibrating life can they live, with Carla casting off the past and Max reclaiming it. They are given their freedom from death; an opportunity to live fearlessly in the knowledge that they are, indeed, alive.

Footnotes

1 Campbell, Virginia. “Love, Fear and Peter Weir.” Movieline Magazine (September 1993).

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon