| Chelli Riddiough |

Shaft plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, August 4th, through Sunday, August 6th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

What’s iconic about Shaft?

The theme song.

The beige turtleneck and brown pleather trench coat.

The sideburns and afro.

The $50-an-hour detective fee.

The fact that detectives are called “dicks.”

The terrible one-liners lauded as wisecracks.

The unnecessary sexual conquests. So Shaft gets laid—what’s iconic about that?

The choker necklace that digs into Ben’s neck.

The mention of “groovy boobs.”

The nonsensical light features.

The flute-heavy soundtrack.

Many things are iconic about Shaft. That list doesn’t include its plot or character development. Fifty-two years after its release, is Shaft outdated or does it stand the test of time? The answer is yes.

At first blush, Shaft is an action movie. That said, it’s incredibly light on action, with few fight scenes or shootouts. John Shaft, a Black cop in 1971 Manhattan, is tasked with finding the kidnapped daughter of a mob boss. He accomplishes this mostly through talking. In fact, Shaft revolves around conversations, many of which are punctured by the slamming of a landline into its cradle.

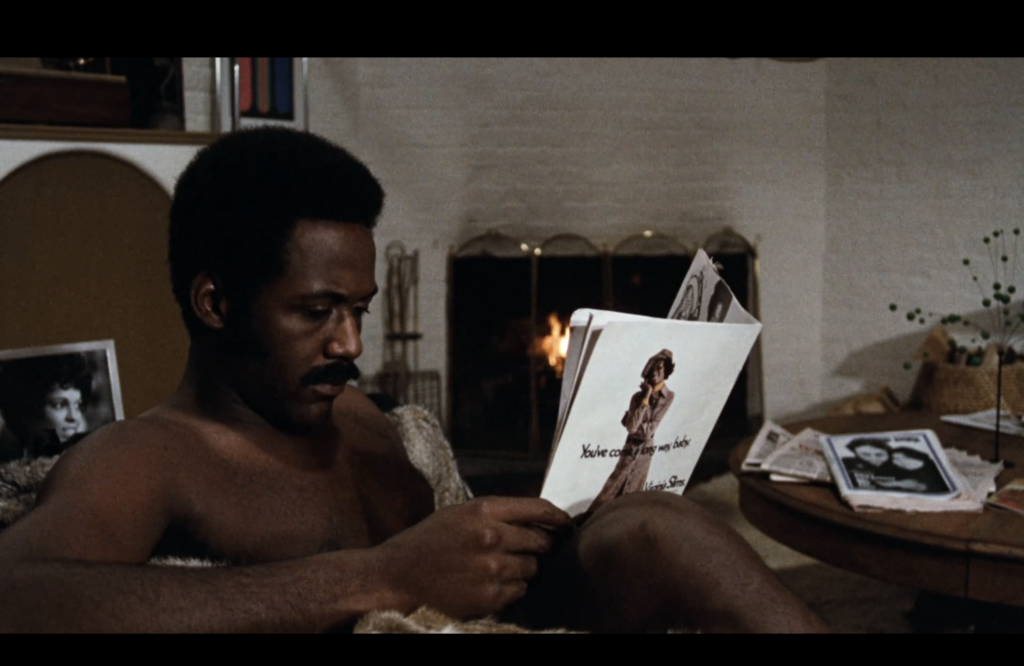

Shaft felt, above all else, slow. Much like Saturday Night Fever, it opens with a long sequence of our protagonist walking down a New York City street. For four minutes, there is no dialogue, just Shaft in his signature turtleneck-and-trench-coat, strolling his way to a newsstand and oozing… confidence? Sex appeal? Something. It’s an unhurried introduction to our title character that a modern film would never allow.

Shaft is known for being one of the first Blaxploitation films, a genre rich with salacious plots and melanin (Full disclosure: I’m a white woman and my lone exposure to Blaxploitation films has been a college screening of Black Dynamite and an awareness of Pam Grier.) In 1971, it was rare for a mainstream film to feature a Black protagonist. It’s still rare. Instead of shying away from acknowledging race, Shaft leans into it: our title character constantly jokes about his own Blackness and calls out his police peers for their whiteness. In a movie rife with mob bosses, I at first thought “Whitey” was another Mafioso before realizing that no, when Shaft and his pals drop that term they’re actually referring to the white majority. Despite its omnipresence, race plays a supporting role in this film. Shaft teases racial tension but ultimately leaves things undisturbed. No race war erupts, as the police department fears. Shaft’s levity about being the lone Black cop in a white world never transforms into anger. No confrontations are had. Racial differences are acknowledged, but in a manner that always feels low-stakes. The movie ends with Shaft laughing and walking away, a perfect image of his (forced?) flippancy.

So: Is Shaft iconic because of its Black lead and its open acknowledgment of race? I called my mom to inquire. She was 16 when this film came out and, I thought, could speak to what made it so popular back in the day. Her answer surprised me: “The theme song, the outfits, and the hair.” In other words, the same exact things that I liked. I had assumed that those were all self-serious aspects of the film that had aged into absurdity. Turns out they were over the top even in ’71, maybe intentionally so. Whether or not Shaft caricatured itself on purpose, by doing so it avoided the worst fate a movie could suffer: not being in on the joke. And as John Shaft might tell you, that’s the worst fate a man could suffer, too.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon