| Eli Holm |

The Conformist plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, July 28th, through Sunday, July 30th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Suspended in anticipation, a man named Clerici sits awaiting his cue, a pawn of a larger game, too terrified to sleep, waiting to strike. He’s in a blank slate of ruin, without discernible emotion, putting on his mask of high-class clothing, tucking his gun, braving the winter air, ready to kill. His final mission has begun. How does one get into this predicament?

The Conformist by Bernardo Bertolucci shows the events leading to Clerici’s state of ruin, bringing us along a mission to consume followers into submission, with false comforts and broken dreams, drowning its members in isolation and waning power. The film proceeds through a series of flashbacks leading to this moment.

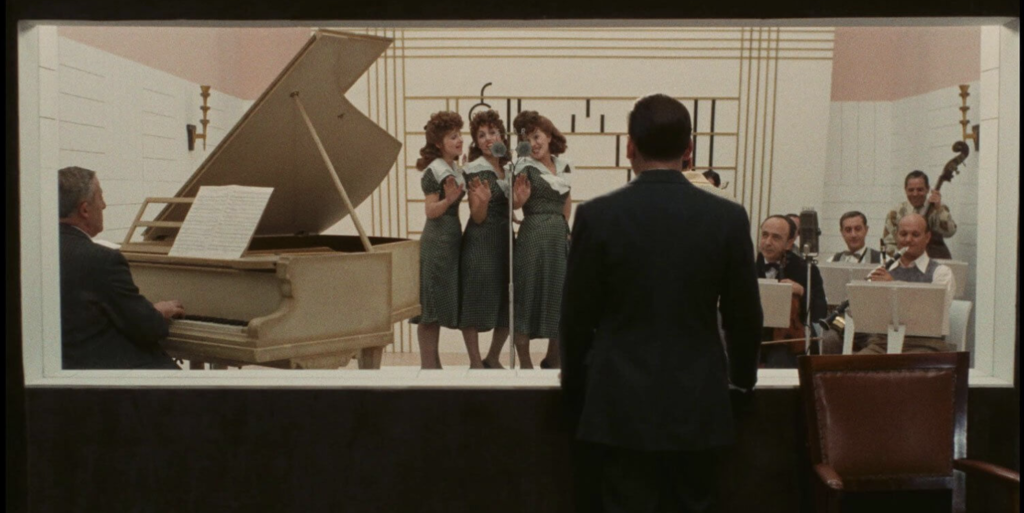

The first flashback is the mission statement of Clerici. He is meeting with his friend Italo, discussing Clerici’s plans to marry in order to create “the impression of normalcy”. Italo observes how Clerici, instead of choosing differentiation, has chosen conformity. “You want to be the same as everyone” Italo remarks. Indeed, Clerici’s mission is normalcy—being the titular conformist. Since this is the first real introduction to Clerici, the film gives us no discernable attributes aside from this choice. He is defined by his devotion to this mission, to be normal by any means.

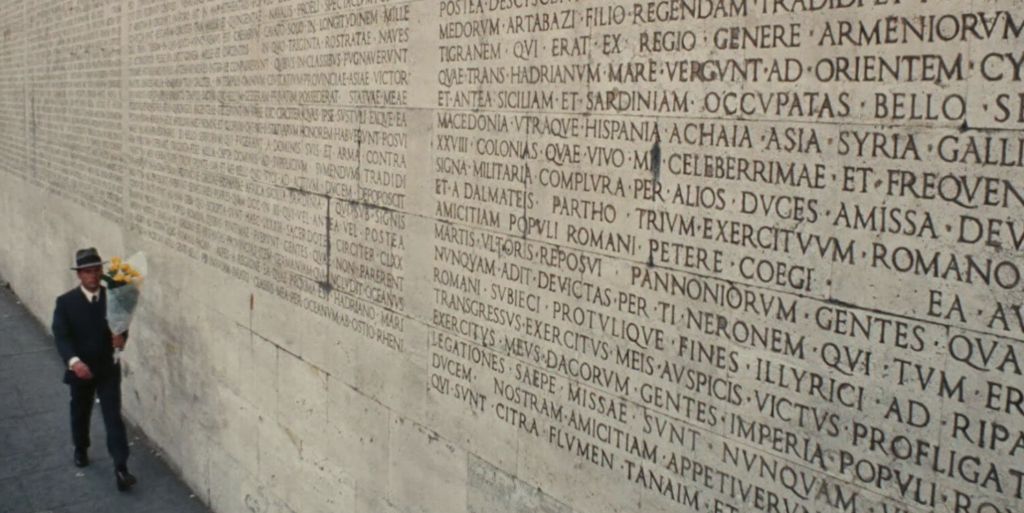

This scene also shows Clerici proclaiming devotion to fascism, revealing his feelings of alienation. In 1930s Italy, striving for normalcy included pledging allegiance to the growing fascist regime—a regime aligned with totalitarianism and ultranationalism, led by the dictator Mussolini. As a way of showcasing power over his state—with the ultimate goal being expansion and domination—fascist leaders often start with the suppression and homogenization of the original state into “model citizens.” Clerici’s goal is to be this model citizen, falling for the propaganda and FOMO attached to the movement.

Fascism as shown in The Conformist brings on punishments for those not willing to conform; severe military presence, castor oil punishment and imprisonment, as well as the devastating effects of this ideology’s failure as a political system, including the economic turmoil and rampant homeless population, haunt Clerici’s environment as he dives deeper.

The next flashback is about Clerici’s childhood, as we see his life molded by trauma and insufficient care. His mom is a morphine addict, and his dad is in a mental institution, for anti-fascist beliefs and emotional instability. It’s a picture of neglect and disarray. If we are products of our environment, Clerici works to become removed from his.

The film reveals one of the most important reasons for Clerici’s drive to conformity when he meets with a priest to confess his sins before getting married. There, he admits to the greatest sin of them all, having murdered a man named Lino who coerced him into sex as a child. Here, the film critiques religion on the same grounds it critiques fascism—for being an institution built on power and expansion, a step towards social normality that seemingly holds your best interests, but, as shown by the priest’s teachings for Clerici to shove his life of sin behind and not examine it, ultimately forces loyalty in exchange for false comforts and inclusion.

When Clerici meets with the professor he’s set to assassinate, they discuss Plato’s allegory of the cave and the theory of subjective interpretation. Seeing the shadows and believing them to be truth without question is like the spoon-feeding of fascism in Italy, forcing only one interpretation in the fluidity. The comfort that comes with reality being one thing and choosing not to question it, is Clerici’s main aspiration. He enjoys being chained to the cave, as it means he holds status within its convoluted structure built on ideological imprisonment. At least he’s chained with others. The professor chooses to disregard fascist shadows, finding peace in subjective interpretation. Shadows can be read in a multitude of ways, but when you’re chained and fed them, the commanded interpretation is all you’ll see. In the final moment, the professor shuts the blinds, and Clerici’s shadow vanishes from the wall. No more does Clerici have interpretive freedom in his shadow, he is Clerici the fascist, believing what he is told to hold status, chained to a wall. The professor says that if Clerici is in fact creating an ideal Italy, then it is of torture and the disregard of human subjectivity.

We catch up with Clerici in the present. He drives the windy roads of the Paris countryside, following the professor and his wife’s car. The secret police stop their car and shoot the professor. Originally, Clerici was supposed to kill him, but his mission was never to help with any fascist executions—it was only conformity.

Cut to 1943, the end of Italian fascism. Clerici is living with wife and child, and we catch them during their nightly prayers. But the radio in the background interrupts them with the news of Mussolini’s resignation. It’s a stunning moment, as we cut from prayers, a moment of normality like Clerici dreamed of, right to his wife, staring at Clerici with disbelief. I imagine her thinking, “Have I really given my life over to this man and his mission, just for it to crumble?” In this moment we see the belief in a life with a man she trusted fall, as the basis of their livelihood was built without any substantial grounding in longevity. We see Clerici teaching his child to pray, and I can’t help but feel cynical about this supposed moment of joy. It seems more like indoctrination, and Clerici reaching out and implanting the hunt for normality into the child’s future. We can only hope the child will work to remove himself from his father’s teachings.

Italo and Clerici meet again and encounter two men flirting—one of which turns out to be Lino. Enraged, Clerici beats him. At this moment, it’s the only way Clerici knows how to regain control, assaulting past trauma in a fit of rage. While I am all for dealing with trauma and putting abuse in its place, the film, again, finds a cynical approach. Instead of relaying a feeling of catharsis, the scene feels sad, showing a powerless Clerici trying to find justice against an evil that brought him to where he is. We have seen his plight to join an evil that pushes othering and oppression, so for him to try and kill what made him feel broken and othered in the first place is like watching an evil run to its source and only find a mirror. Lino created an oppressive otherness that Clerici needed to fill, thus turning to fascism, a system pushing otherness and that same oppression. Now that this system crumbles, Lino gets the last laugh, knowing he created this push to evil; knowing he survived Clerici’s first attempt to kill him, and so will also survive this one. Clerici was a pawn of evil all along, starting him young on a quest to escape his demons, but in reality, only creating and accepting new ones into his life through his belief in crumbling oppression.

Clerici, in shambles, sits in front of a prison cell, turns around, and sees the man Lino was with, naked on the bed. It’s like Clerici staring into the past, recognizing the moment when he found his truth infected by evil, but he can’t do anything about it, as he has become just as evil as Lino. So he can only sit there, recognizing the infection spread within this man living his truth, but knowing full well he has done the same thing to many. He was created by the oppression exercised by Lino. This is the product staring back at him: an angry man, fed up with fascism and sick of hiding his truth. The film cuts to black, and we are left in anticipation, Clerici has no sway here, and the man’s rage is intoxicating.

Clerici rose with fascism, and is now watching it crumble, his future uncertain, and his power gone. Despite the film’s structural set-up as a search, we never see Clerici work toward anything; we only see him used as a pawn to fascism, swayed by FOMO and craving inclusion. The foundation of Clerici’s beliefs comes from being chained by oppression and fabricated comfort, in turn chaining others, dragging himself and his circle deeper into the fires of oppression, and coming out the other side with nowhere to go. Maybe he joins another movement; maybe he finds a purpose in family; maybe he and the man shake hands and go their separate ways. But I think we know better. He ends up sunken and alone, he has seen outside of Plato’s cave, and there is no place for him.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon