| Chris Ryba-Tures |

The Conformist plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, July 28th, through Sunday, July 30th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

To wear a mask is to literally put on a second face, a second identity—a theatrical identity removed from the everyday world.

Lesley K. Ferris, Masks: Faces of Culture1

Little soul, little wanderer, peeking out / from my body’s cover, host and lodger / which now change place

Hadrian, “Animula Vagula Blandula”2

I know I’m not the same person I was when I put on my first N95 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Before masking, I felt helpless, exposed, terrified to my core. People were dying by the thousands. Those who weren’t dying were getting sick, losing their memory, their senses, their ability to think clearly. While some folks lost their jobs and their homes, others were being worked to death. People were turning their backs on science and medicine. There were quarantines, curfews, and mask mandates. There was an insurrection.

I know I’m not the same person I was before the pandemic, but I’m still not sure who I am now.

Navigating a world in the throes of functional chaos where “normal” seemed a thing of the past, masking felt like a step toward order. I embraced it, prioritized it, and made sure I always had a mask within reach. Masking gave me a sense of control, of stability and safety and, eventually, an identity. Although the mask first declared my alignment with the new normal, it soon became a lodestone for (highly reductive) judgments: A masked person cares about themselves and others; an unmasked person cares only about themselves. A masked person believes in science; an unmasked person believes dinosaur bones were put there by God to test our faith. A masked person is willing to put their own comfort aside for the common good; an unmasked person demands all the accommodations afforded by individual freedom at all times.

I started to prefer masking. Not only did I have a contextually relevant black-and-white way of looking at the world, I could disappear from that world in plain sight. I could be a different version of myself—one who didn’t have to extend so far into society. I didn’t have to get a laugh out of barista or fill elevator silence with polite chatter. I didn’t have to engage with anyone. In fact, the CDC suggested we all keep 6 feet away from each other. I started to equate this distancing with more than just safety from exposure to disease—it was safety from exposure to other people. It didn’t take long for all of this self-protection and judgment to feel normal. And since masks were required everywhere from hospitals to buses to grocery stores, it looked normal too. But normal—our understanding of it, our definition and expectations of it—changes constantly. And when it does, we have to remove our old masks or risk suffocating.

The most frightening thing about taking off our masks, regardless of our reasons for putting them on in the first place, is seeing who we are once they’re off, what’s left of who we were, and what exactly it is we’ve allowed ourselves to become. This was top of mind when I took a closer look at Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1970 quiet thriller/political drama The Conformist. It was the Spring of 2023—a time when I was the only person still masking (and suffocating) in a workplace of 300 people.

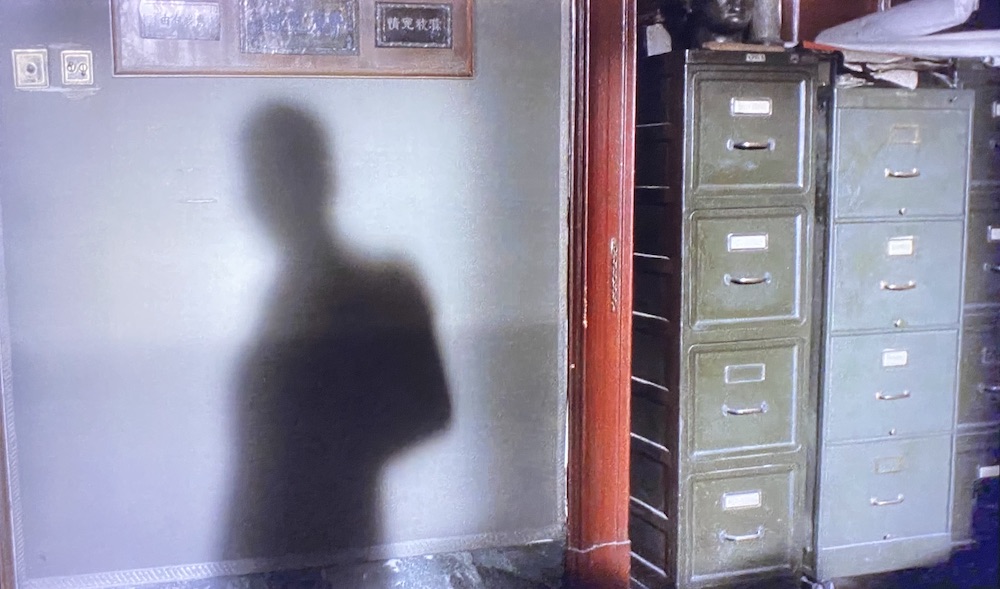

The story centers on Marcello Clerici—a privileged man desperately donning the mask of a model citizen in Mussolini’s fascist Italy—who proposes an extreme demonstration of loyalty to the secret police: he will assassinate his former philosophy professor, currently a political refugee in Paris. While the film’s story mostly takes place during the short distance between the “green light” for the hit and the hit itself, it is repeatedly interrupted by flashbacks as Clerici revisits moments in his past that substantiate this ideologically-driven mission. Many of these moments directly reinforce his performance of fascist conformity. Anything contradictory or threatening to this performance is omitted from the main action, but it still lingers in the periphery; there are numerous moments within those moments that suggest Clerici might not be the “normal” fascist he aspires to be.

Early in the film, when describing getting dressed in the morning (a process of both covering and costuming) he laments, “In the mirror I see myself, and compared to everyone else, I feel I’m different.” Shortly thereafter, he mumbles to himself the opening lines of the death poem Animula Vagula Blandula in which Roman emperor Hadrian says goodbye to his soul that is “peeking out from [his] body’s cover.” Clerici becomes visibly panicked when an anonymous letter arrives detailing a damning entry in his family’s medical history. One small, telling act after another reveals how desperate he is to hide behind the facade of a normal life—the messiness of individuality, the shame of a traumatic past, the fear of being clearly seen.

Clerici’s mask—an amalgam of high-minded fascist philosophy, a stoic demeanor, drab tailored suits, and manipulatable relationships—is painstakingly fashioned to help him cover up his individuality in order “to build a life that’s normal.” He guards himself, physically and emotionally, against those nearest to him—from community, from exposure, from vulnerability, from nakedness. And, by the time we meet him, he’s done a pretty good job of it.

He’s swapped out his past as a serious, free-thinking philosophy student for the dogmatic myopia of the fascist party to help him achieve a “normal state.” His marriage is a tool to help him achieve “the impression of normalcy.” His fiancée/wife, Giulia, appears to be a patriarch’s ideal: “A petty bourgeoise […] mediocre. A mound of petty ideas […] all bed and kitchen.” His best, and seemingly only friend, Italo, is a visually impaired radio announcer who continually reinforces their shared commitment to the party line. And, most impressively, Clerici has managed to keep the lid on his still-bubbling shames and traumas, including the bullying and sexual assault of his childhood, his first (attempt at) murder, his drug-addicted mother, his institutionalized father, and a multitude of other unnamed sins.

Any time anyone mentions normalcy or fascism (which are the same to Clerici), he reinforces his commitment to them. Even when the mask slips, when shows a glimpse of the man behind it in moments of confession, cruelty, and bizarre behavior, he has worn it so convincingly, with such conviction, and for so long that no one seems to question his performance.

But we do.

We notice that Clerici is rarely undressed, even during sex. He delights in tormenting dogs. He poses childishly when issued a handgun. He mocks his mother’s servant/lover/drug dealer with a teenager’s malignity after having him “removed.” He tenderly embraces a strange prostitute. He molests his fiancé as she confesses her own sexual abuse as a child. We see him increasingly uncomfortable in the company of others, especially crowds. We watch him plan to assassinate his former philosophy professor, sexually assaulting and stalking his target’s wife, Anna, in the process.

Normalcy, no matter how well crafted, cannot contain such untended human messiness.

As we notice these things, the mask slips further. Clerici spends more and more time staring into the middle distance. He tries to back out of his mission, he waffles, he recommits. We start to believe Anna’s accusation that he is a coward. The hit will go on, but whether Clerici will follow through is yet to be seen. At the pivotal moment, his mask is lifted, the coward is revealed. He balks. A dozen other fascist stooges, indiscernible from each other, take action where Clerici could not.

Time passes. Fascism falls. People change. Mussolini’s head is cut from a statue and dragged through the streets. The old normal is supplanted by a new one. In it, we see Clerici, still masked, but wearing a different costume; a Clerici steeped in true mediocrity and dressed the part. All of it is ill-fitting.

In his ultimate moment of revelation (and betrayal), his past appears and tears off his mask for good. Clerici is laid bare, naked and screaming. His few remaining strands of self are gnarled by Fascism, atrophied by ambition, a mass of fear and rage with a puddle of his untended humanity pooling at his feet. In the final, isolating moments of his story, we are left to wonder what will happen next. Can a new person grow out of this desolation? Can this exposed, underdeveloped, neglected mass of cowardice and trauma be shaped into something more alive? Will Clerici finally “be excused by society” as he’d once desired?

Is there any excuse for him? Any forgiveness? Any hope?

Masks, from N95s to workplace faces, from the political landscape to the family dinner table and the comments section, help us navigate our circumstances; they help us gain a sense of control and find a more comfortable place in our respective ideas of normalcy. Each brings its own protections and prices, privileges and punishments. In this dim light I was able to scrounge up some empathy for Clerici. But I’m not ready to excuse him. And I’m far from forgiving him.

In the final moments of the film, when the mask is off, the performance is over, and Clerici and I are sitting alone, six or so feet from other strangers in the dark, I am guarded. Maybe I haven’t fully come out from behind my own mask. Maybe I’m afraid to face what’s left of me, what I’ve lost, what’s pooling at my feet, even now.

Bibliography

1 Ferris, Lesley K. Masks: Faces of Culture. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999. 231.

2 Hadrian, Anima Vagula Blandlua, 138 CE, trans. David Capps, 10 Translations of Hadrian’s Animula Vagula Blandula, 2020, https://www.academia.edu/43690540/10_Translations_of_Hadrians_Animula_Vagula_Blandula

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon