| Matthew Tchepikova-Treon |

Lady Snowblood plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, June 2 through Sunday, June 4. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

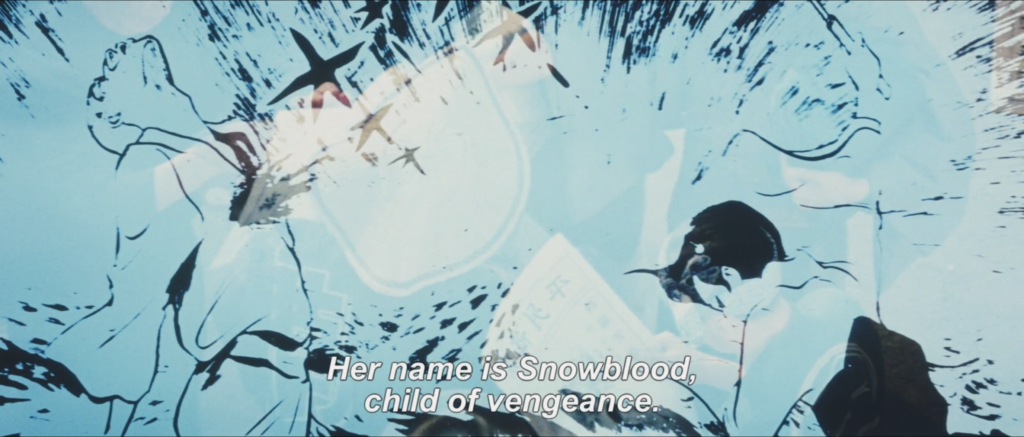

The year: Meiji 7 (1874). Inside a Tokyo prison during a snowstorm, we hear sharp winds, a dying woman’s anguished howling, and the cries of a newborn baby girl: Yuki. Outside, through a wood-barred window, white snow falls against a pure black backdrop. The snow turns red. A title splashes across the screen: Lady Snowblood (修羅雪姫). The single strike of a hyōshigi (a traditional Kabuki theater percussion instrument) marks a twenty-year flash forward. At night, on a narrow road among sparse trees, Yuki walks through the quiet snow, her iconic purple umbrella spread overhead. She approaches a small cadre of officials, all men, pulling a rickshaw in the opposite direction. They command her to move. Yuki instead slides a sword from her umbrella’s handle. Within seconds, a severed arm, a slit throat, a fatal stab through the stomach. She ends each man’s life with balletic ferocity. The man in the rickshaw, with his final breath, asks, “Why?” “Revenge,” Yuki responds. “For the powerless people you made suffer.”

Two specters haunt the world of Lady Snowblood. On its pulpy surface, the film tells the blood-splattered saga of a classically tragic character, Yuki, who hunts down the gang of bandits that murdered her father and raped her mother. At the same time, set during the Meiji Restoration, when Japan transformed from a feudal society into an industrialized, techno-imperialist nation—commencing in 1868—its story also conjures the regal bloom of Japanese nationalism against the backdrop of both agrarian mythos and late-Cold War militancy. In other words, Lady Snowblood is a century-long ghost story expertly cut down to ninety-seven minutes of quiet convulsive rage.

Yuki’s retribution tale entered the Japanese popular imagination in 1972, first published as a serialized manga in the pages of Shūkan Pureibōi (Weekly Playboy), an adult magazine inspired by, but not actually a regional edition of, Hugh Hefner’s Playboy. Written by Kazuo Koike (Lone Wolf and Cub) and illustrated by Kazuo Kamimura, the original story spanned fifty-one issues. Before the final installment ran, Tokyo Eiga producer Kikumara Okuda, in the market for a politically-minded piece of adult fare to pitch to the popular singer and exploitation film star Meiko Kaji, set out adapting Lady Snowblood for the screen.

By 1973, Kaji was well known for her steely-eyed portrayal of pulp-dramatis personae associated with all manner of vice and formerly codified prohibitions. Working with eventual Lady Snowblood director Toshiya Fujita, she had launched her acting career as a leather and denim-clad dissident in Stray Cat Rock, a series of low-budget American-styled rock’n’roll films produced at Nikkatsu studios. Kaji then moved to Toei Company, staring in a trilogy of chic “women-in-prison” films titled Female Convict Scorpion. She even recorded the first film’s theme song, “怨み節 (Urami Bushi),” which became a popular seven-inch release in its own right. Notably, these early films evinced the complicated popularity of American culture during U.S. occupation of post-war Japan. Their unruly protagonists and audiences alike tended to identify with the emergent left-wing youth movements, post 1968, especially concerning anti-war sentiments. Yet still, their inherited signifiers of artistic rebellion helped build a pop-culture palisade meant to defend against right-wing groups calling for the return to a so-called “pure Japan.” Amidst these absurd, violent, and often bawdy films, Kaji stood out as uniquely cool and thus maximally malcontent.

Enter the “asura demon” and her small band of Meiji radicals.

First and foremost, Lady Snowblood draws on Japan’s long tradition of chanbara (sword fighting) films, conventionally set in the Tokugawa and Meiji eras. Following the second world war, such films began to explore themes of cultural disillusionment and social alienation, while many Japanese filmmakers, most notably Akira Kurosawa, likewise began experimenting with more stylized techniques in both the visual and sonic registers, particularly when it came to exaggerated on-screen violence. Along with the barrels of cherry-red blood spraying from dissevered arteries, Lady Snowblood is saturated with a distinctive melange of traditional Japanese music, funk-psychedelic vamps, avant-garde sound design, and grotesque foley work. Firmly situated in its own cultural moment, the film’s lasting allure, I’d say, nonetheless stems from this mingling of period-piece storytelling and anachronistic stylings.

In fact, it’s the loopy whorl of time and aesthetics that animates Lady Snowblood’s world-historical charge. There is of course the conspicuous theme song, “Shura No Hana (Flower of Carnage),” from the opening credits: We see a sweeping montage of Yuki training with a Buddhist priest before striking out on her own. All the while, Kaji’s voice skirts atop a glossy blend of kayōkyoku (a form of pop song specific to post-war Japan) and enka music (a style rooted in the Meiji era), singing beautifully about grief, solitude, and murder.

But within the film’s frenzied refashioning of Japanese history, one ghostly scene in particular stands out as the strangest and most chilling, when Yuki artfully slices in half the lifeless body of a woman who has hung herself. Blood pours out of the bisected torso and we hear the single strike of an okawadrum—common in Kabuki theater—accompanied by the heavy draw of a reverb-drenched guitar line, before a curtain suddenly lowers, creating the implication of a proscenium arch while drawing the scene to a close. It’s a singular moment of literal theatricality that gets to the heart of Yuki’s conflict, understood here as a larger clash between Japan’s agrarian past and a violently displacing modern world.

After WWII, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, serving as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, sought to ban Kabuki theater as a relic of Japan’s feudal society, i.e., of “pure Japan.” However, a scholar, writer, and musician named Faubion Bowers, who served as a translator for MacArthur, managed to successfully defend its preservation by convincing the general that Kabuki was too rich an art form, too historically significant to dispel from the modern world. Thus, in a fittingly circuitous way, the Kabuki-styled set-piece in Lady Snowblood recalls how the Empire of Japan paradoxically rejected modernity at the height of its power entering WWII, calling for a return to a pre-modern Japanese spirit. It was, in essence, a call for purification echoed again by political leaders in the 1970s… then again and again. As Meiko Kaji sings in the opening credits of Lady Snowblood, “Yesterday and tomorrow hold no meaning, I’ve immersed my body in the river of vengeance.”

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon