| Dylan Walker |

The Dirty Dozen plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, April 2 through Tuesday, April 4. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Warning: Spoilers below for The Dirty Dozen and The Last of Us video games (particularly Part II).

While I’m not really a video game person, I’ve been intrigued by The Last of Us franchise thanks to a coworker who sings its praises, positive reviews of the HBO show, and a mild crush I’ve developed on Pedro Pascal. So, the other day, I decided to spend some time on YouTube checking out gameplay footage.

Did I choose to watch touching clips of Joel and Ellie’s developing relationship? Maybe Ellie and Dina falling in love? Nope. Instead, I was out for blood.

After thirty minutes of watching people beaten with golf clubs, fingers bitten off, and lots of NPCs torched with Molotov cocktails (all while skipping the crouching and lurking in order to get to the good stuff), I found myself wondering what the heck I was doing. Why was I searching for murder and gore specifically? Most disturbingly, why was I titillated by the rampages and acts of revenge? I was afraid of seeing graphic details, and yet I found myself disappointed when the camera cut away from the worst of them. I was hoping to feel something, but all I felt was numb and blank.

Afterward, I compared the experience to watching The Dirty Dozen (1967). In preparation for this post, I’d rewatched it a few weeks before, and Robert Aldrich’s testosterone-filled World War II flick (complete with an all-star cast and its own share of violence that appalled contemporary critics) had inspired some similar feelings.

I honestly couldn’t tell you the first time I watched The Dirty Dozen. It’s been a staple of my life the way some children attached themselves to Spongebob Squarepants and Disney movies. Any time it aired on Turner Classic Movies, especially every Memorial Day, my dad and I gathered in the living room with a bowl of popcorn and watched it. In my research of the film, I was surprised that contemporary critics described the film as “delightfully sadistic, brutal, inhuman”[1] and “an astonishingly wanton war film.”[2] Preparing for a spectacle that would horrify me and cause me to wonder what my dad was thinking, I entered the film with trepidation.

Scarier to me than what was happening onscreen, though, was my reaction to it. I felt the same way I did about the violence in The Last of Us — numb and blank.

In a 1976 interview, filmmaker Pierre Sauvage asked director Robert Aldrich if his films accurately conveyed his anti-war and anti-military viewpoint, using the aforementioned critical response to The Dirty Dozen as an example. Aldrich mentioned the scene that so incensed Roger Ebert in which Jefferson (Jim Brown) throws hand grenades down ventilation shafts that have already had gasoline poured down them in order to blow up the German officers and their wives and mistresses who are hunkered down in a bomb shelter. He added:

“Now, what I was trying to do was say that under the circumstances it’s not only the Germans who do unkind and hideous, horrible things in the name of war, but that Americans do it and anybody does it. The whole nature of war is dehumanising. There’s no such thing as a nice war. Now American critics completely missed that, so they attacked the picture because of its violence, and for indulgence in violent heroics.”[3]

According to Aldrich, the violence is justified as a delivery mechanism for the message that there is no glamor in war, whether you’re a “good guy” or a “bad guy.” Once again, I think of The Last of Us, specifically the second game. A meditation on revenge and violence itself, some criticized the extreme gore in Part II upon its release. For co-creator Neil Druckmann, this is part of the point.

“I was like, ‘Oh, we can make the player feel that. We can make you experience this thirst for revenge. This thirst for retribution and having you actually, like, commit the acts of finding it and then showing you the other side to make you regret it. To make you feel dirty for everything you’ve done in the game, making you realise ‘I’m actually the villain of the story.’”[4]

There is no glamor in vengeance, whether you’re a “good guy” or a “bad guy” and no matter how badly you feel you deserve it.

As much as I love watching The Dirty Dozen and The Last of Us gameplay, and as much as I sympathize with the intent, I’m not sure the impact lands as the condemnation Aldrich and Druckmann were hoping for. Let’s look at The Dirty Dozen. While overall an anti-establishment commentary, the titular Dirty Dozen and their commander, Major John Reisman (played by a stellar Lee Marvin), enact violence toward each other in ways fairly stereotypical of a macho Hollywood film. To prove his toughness and ability to command a unit of violent criminals, Reisman throws Franko (John Cassavetes) to the ground and stomps him in the face a few times. Posey (Clint Walker) starts the movie as a gentle giant afraid of his own strength but later proves his worth by smacking around soldiers attacking Wladislaw (Charles Bronson) and gunning down carfuls of Nazis. Weak men prove their strength by punching others and Reisman threatens to beat people’s brains out for the crime of disrespecting him. I would argue much of this would go unnoticed by critics if it weren’t for the brutality of the Dozen’s suicide mission and the occasional pictured “taboo” violence such as the hanging that opens the film, the way Maggott (Telly Savalas) kills a German woman in cold blood, and the onscreen deaths of Pinkley (Donald Sutherland) and Vladek (Tom Busby). The rest of it is taken as standard operating procedure and goes uncriticized.

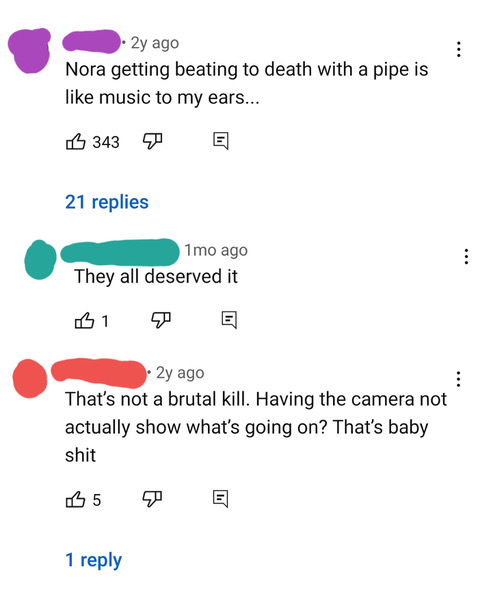

As for The Last of Us? Many people seem to have missed Druckmann’s point. According to the YouTube comments, it appears I’m not the only one with a case of bloodlust:

Credit: YouTube

“Nora getting beating to death with a pipe is like music to my ears…”

“They all deserved it.”

“That’s not a brutal kill. Having the camera not actually show what’s going on? That’s baby shit”

I wholeheartedly agree with messages that are anti-war and anti-revenge. I also don’t agree with censorship and believe Aldrich and Druckmann aren’t responsible for consumers misinterpreting their intended messages. Furthermore, I think the human desire to test ourselves with exposure to violence is natural, especially when we are so surrounded by violence every day; so I’m not going to report myself or anyone else who consumes violent media.

Multiple things can be true. I think the storytelling in The Last of Us is beautiful, and I can’t wait to start watching the TV series. I love watching the cast in The Dirty Dozen begin the movie as individuals but come together as a team by the end of the movie, and I can’t wait to watch it on the big screen at the Trylon. I admit that something about violence excites me, and I am also afraid of what my own and others’ desensitization means.

At the same time, I am troubled by the nonchalant presentation of violence as a means to an end. I feel like many creators want to have it both ways, relishing in portraying abuse with close-ups of boots coming down on a face and lovingly animated blood spray while condemning it in the next breath. The Dirty Dozen and The Last of Us don’t provide solid answers in this conversation, but they certainly raise many questions.

NOTES

[1] Roger Ebert, “The Dirty Dozen,” Roger Ebert (July 26, 1967), accessed March 17, 2023, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-dirty-dozen-1967

[2] Bosley Crowther, “Screen: Brutal Tale of 12 Angry Men; ‘Dirty Dozen’ Rumbles Into the Capitol,” The New York Times (June 16, 1967), accessed March 17, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/1967/06/16/archives/screen-brutal-tale-of-12-angry-men-dirty-dozen-rumbles-into-the.html

[3] Pierre Sauvage, “Aldrich Interview,” in Robert Aldrich: Interviews, ed. Eugene L. Miller, Jr., and Edwin T. Arnold (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004), 103-104.

[4] Sam White, “The Last of Us Part II: how Naughty Dog made a classic amidst catastrophe,” British GQ (June 9, 2020), accessed March 19, 2023, https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/culture/article/the-last-of-us-part-ii-neil-druckmann-interview

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon