| Nick Kouhi |

That Day, on the Beach plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, March 26 through Tuesday, March 28. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Warning: plot spoilers below!

François Truffaut once claimed that every director’s film is a remake, more or less, of their first feature. Such an assertion suggests that to truly understand any auteur’s intentions, one must return to the crucible from which their art was forged. This is a useful tack to adopt when studying any filmmaker with a recognizable signature, but it also betrays the depths one can plumb in an auteur’s autumnal output. I can’t help but wonder, for example, what Truffaut would have said about Edward Yang’s Yi Yi (A one and a two)? It would have been the only film in Yang’s small yet formidable corpus that Truffaut, like most cinephiles in the West, would have seen in the Taiwanese master’s lifetime. But we can only speculate, for Yang, like Truffaut, didn’t live past the age of sixty. His death from colon cancer is an immeasurable loss to world cinema.

Blessedly, the restorations of Yang’s other six features have made the most cosmopolitan of the Taiwanese New Wave filmmakers more accessible to a global audience. Yang’s genius as a surveyor of the historical conditions of his native Taiwan can now be more clearly mapped between his prescient studies of globalization’s psychic impact on our most intimate connections. Case in point: Yang’s first film, That Day, on the Beach, established his longstanding preoccupations with collective and individual identity in Taipei at the end of the twentieth century. Formally and narratively, the film is both of its time and also evades a strictly linear perception of time’s impact on self-recognition.

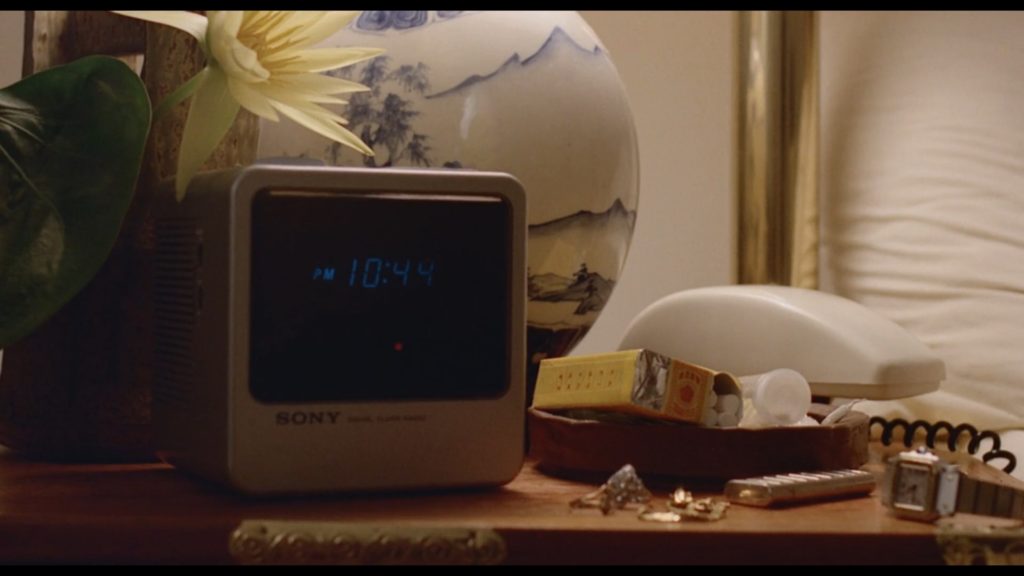

From the opening moments, we are thrust into a living memory without knowing that the silhouetted figures we watch cluster around an unseen object washed ashore is neither the first nor last moment to chronologically occur in the film’s temporally discursive narrative. When we see a digital clock nested on a bedside table in the ensuing shot, it’s the first indication that we are about to watch a film which features, in the parlance of Godard, beginnings, middles, and endings, though not necessarily in that order.

But I’m getting ahead of (or is it behind?) myself: the plot properly commences with the reunion of two women, Wei-ching (Terry Hu) and Jia-li (Sylvia Chang). The former dated the latter’s brother, Jia-Sen (Ming Hsiang-Tso), when they were young adults, before their romance was squelched by his and Jia-li’s father (Nan Chun). Wei-ching’s heartbreak drove her into pursuing a successful career as a world-traveling concert pianist. Her return to Taiwan after 13 years provides a clear parallel to Yang’s tenure as a student in the United States for the better part of a decade before he returned to Taipei with his sights set on making films.

While the opening passages of That Day, on the Beach suggest that Wei-ching will be our central character, Yang pulls the first of several narrative coups by putting Jia-li at the fore of the film’s ensuing flashbacks. We revisit her early courtship with De-wei (David Mao), a fellow student she met while studying language arts at university. She elopes with De-wei, partially out of genuine love and partially to escape the fate her brother faced when wedded in an arranged marriage and forced to follow in the footsteps of their physician paterfamilias. Yet, almost immediately, we leap further in time to a horrendous development: De-wei has been reported drowned off the coast of the eponymous beach which, we soon realize, will provide the film its central mystery of what exactly happened to the man Jia-li loved.

Marriage Story: David Mao and Sylvia Chang

The epistemic ramifications of that question transcend the procedural as we plunge into moments of marital strife which widened the gulf between Jia-Li and De-wei. The schism which spelled the end of the honeymoon period was sparked by De-wei’s entry into the corporate world, taken under the wing of his licentious college friend Ah-tsai (Hsu Ming). Yet, the more information we glean about these characters, the more we realize how useless it is to ascribe a given moment any undue significance as a form of explanation. Yang would hone this attitude in his postmodern nightmare The Terrorizers and his sprawling opus A Brighter Summer Day as he proved his mastery in vivifying slow-burn societal parables which ultimately result in shocking yet unsurprising violence.

The alienation and rage coursing through Yang’s filmography is laid bare in the central passages of domestic arguments and confrontations in That Day, on the Beach. When De-wei takes Jia-Li on a reckless cruise through the streets of Taipei, she clutches the dashboard as we cut from her fearful expression to phantom carriage shots of the rapidly unfolding causeways their car barrels through. “You wouldn’t be afraid if you trusted me,” De-wei coldly chides her after stopping the car. It’s as emotionally violent and chilling a moment as any in Yang’s work, transforming a seemingly loving yet troubled partner into someone who possesses untold swaths of fury and entitlement.

from left to right: Tsu Ming as Ah-tsai and David Mao as De-wei

Those twinning impulses emerge in moments of relatively quieter menace, exacerbated by the public sphere of capitalist, patriarchal industrialization. Ah-tsai constantly chides De-wei with the brio of a frat bro when he isn’t threatening to throw De-wei under the bus should his friend’s personal life jeopardize his own business interests. As Ah-tsai makes nepotistic promises over drinks, De-wei’s blank expression is complemented by the faint, diegetic din of David Gilmour’s guitar solo from “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2.” De-wei’s identity is interchangeable with the antihero from Pink Floyd’s 1979 rock opera The Wall, their shared alienation dulling their isolation into a frightening mass of self-loathing.

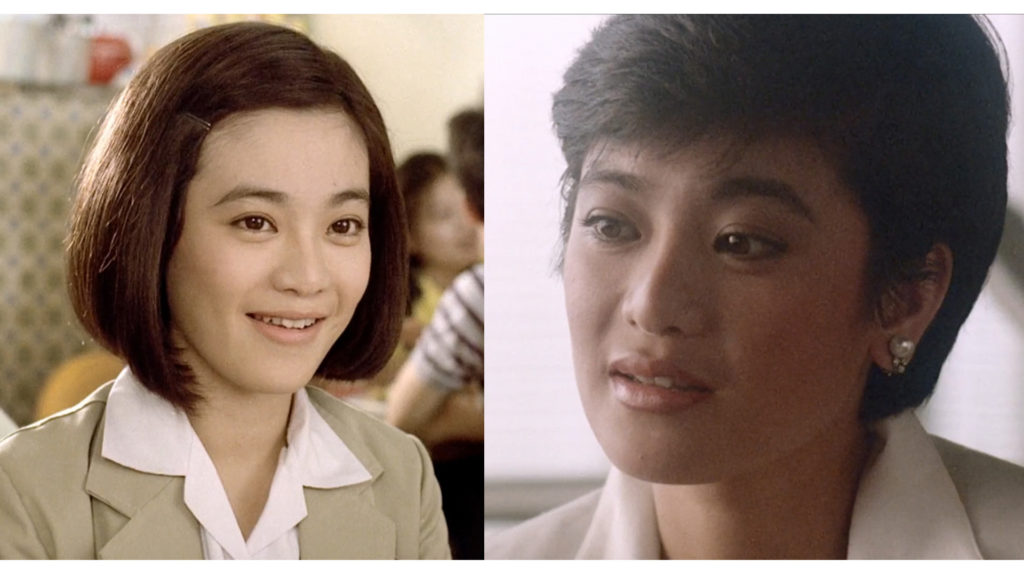

Yet the film’s most crucial passages of existential crisis are faced by Jia-li outside of her marriage. The conversations she shares with other women, including old college friend Hsin Hsin (Lee Lieh), her husband’s mistress (Yan Feng-chiao), and her mother (Mei Fang), invariably return to the myriad ways their lives have been forcibly molded to patriarchal expectations. “The whole society seems designed to tear men and women apart,” Jia-li tearfully confides to Hsin Hsin, laying bare her anguish in uncharacteristically didactic terms. More effective is when Yang, still refining his skill as a writer, lets his actresses express through their body language what words cannot. Chang is especially compelling as she ages several decades in the film through the subtlest shift in her posture, conveying years of hardship, disappointment, and, ultimately, resolve.

Sylvia Chang as Jia-li in the past (left) and present (right)

That final expression in That Day, on the Beach reflects the well-worn optimism of its writer-director. Edward Yang’s humanist liberalism affords all of his characters varying degrees of empathy as they struggle against the categorical limitations set upon them by a rigid social hegemony. Even antagonistic figures like Jia-li and Jia-sen’s father, responsible for perpetuating the tenets which will hurt his children, dies with the hope that his son will be able to carry on his legacy. Anemic to Yang’s outlook is a calcified bitterness, articulated with calculating coldness by Yan’s mistress. “The world I grew up in taught me that it’s a world without love,” she sneers at Jia-li.

Yet for Yang, love is inextricable from knowledge. In conversation with John Anderson, Yang described his philosophy on education as one where “knowing more is simply the process of enjoying life… Before we are anything we are just human beings living in the twenty-first century.”[1] Near the film’s end, as Jia-sen lies dying from cancer, he whispers in voiceover, “I want so much to know it all from the start.” Yang doubtless understood that longing, and it pains the heart to wonder whether those thoughts coursed through his mind as he lay dying from cancer.

But that is a mystery which we will never solve. Life is full of such unexplained questions. The only question we can hope to resolve is, arguably, the question of the self. As Jia-li lets go of her husband’s disappearance and moves forward into a new millennium, we are reminded as we see her leave our lives of the final moments in Yi Yi, when the boy Yang-Yang tells his grandmother at her wake, “Do you know what I want to do when I grow up? I want to tell people things they don’t know.” That desire is a constant at the beginning and end of Edward Yang’s filmography, but I won’t dare put such a final point on this reflection. The generosity of his work is its refutation of finality in affirming existence as a continuum of understanding who we are as we stumble, sometimes into grace, through the world.

NOTES

[1] Edward Yang, “An Interview with Edward Yang”, interview by John Anderson, ‘Edward Yang’, 2005

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon