| Chris Ryba-Tures |

Watership Down and The Plague Dogs play at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, March 24 through Sunday, March 26. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

“We prefer to believe that cruelty occurs only in faraway places.”

—Bessel van der Kolk, M.D.[1]

I was about five the summer the last of my grandparents died. All four died over two years, alternating sides of the family. In our house death wasn’t just a teary conversation to have with the kids after the family parakeet dies. It was a force that rendered my usually warm parents stone-faced and curt, pulling us all across state lines and into dour church basements to sniffle with family we wouldn’t see again until the next funeral. To that point, though, death was an explanation for why we were going on another singalong-bereft roadtrip, who was in the coffin this time and why we wouldn’t be able to visit them anymore.

The last of the deaths took us to Des Plaines, IL, for the funeral of my dad’s dad, a former nurseryman. On the drive back to Saint Paul, my dad told us about being out on the tractors as a kid and how even back then his dad kept him away from the pesticides, the kind of noxious, heavy-duty stuff that filled lab rats with tumors. He was right to do it. It was likely responsible for the Parkinson’s-induced dementia that took my grandpa down in the end.

When we got home from Illinois, a great white dog had appeared in our neighbor’s yard: Nemo. Stalking back and forth on the other side of the chain link fence, Nemo seemed to me and my little sister like some kind of fascinating, possibly dangerous, zoo animal. We kept our distance. At times, while playing in the yard, we’d see a sudden white blur as the beast raced across the yard in pursuit of some ball or squirrel. Usually to no avail.

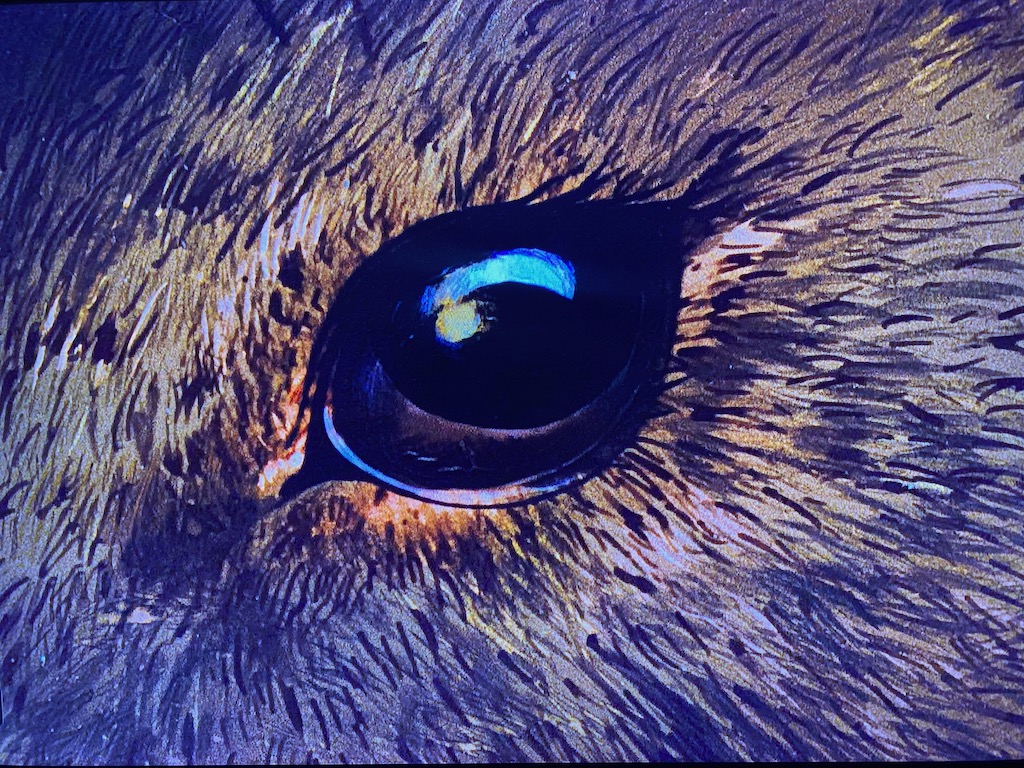

It wasn’t long after our return that it happened. I was the first to see the mauled thing thrashing in the grass in our backyard. In its frenzied flailing, I could see its fluffy white tail, its long soft ears, its black marble eye, and its kicking legs covered in blood. A rabbit. I stood at the window, fascinated, horrified. At some point my sister joined me at my side and began crying. I heard my dad somewhere behind me say, “Ah, shit.” The next thing I knew I watched him, a giant in yellow rubber dish gloves, carrying a bucket of water out into the backyard. He knelt down next to the rabbit, almost in an act of attrition, as he did the grim, merciful thing.

The drowning went on for ages.

When he pulled his gloved hand out of the bucket and stood up, when the violence stilled, that’s when I started crying. I remember that. The finality released the tears, but it was the unnatural violence that gathered them. The brutality. This aspect had been omitted from all the dying of the previous two years. It was ugly and messy and desperate. In a wordless pit in my gut I understood the doomed rabbit wanted more than anything to fight for its life or, at least, to die on its own terms. My dad’s intercession, though well intentioned, felt completely at odds with how I understood the order of things. Nemo, the rabbit, my dad, the fence, and the bucket all met at the intersection of the human world, the domesticated world, and the wild world—and something violent happened there.

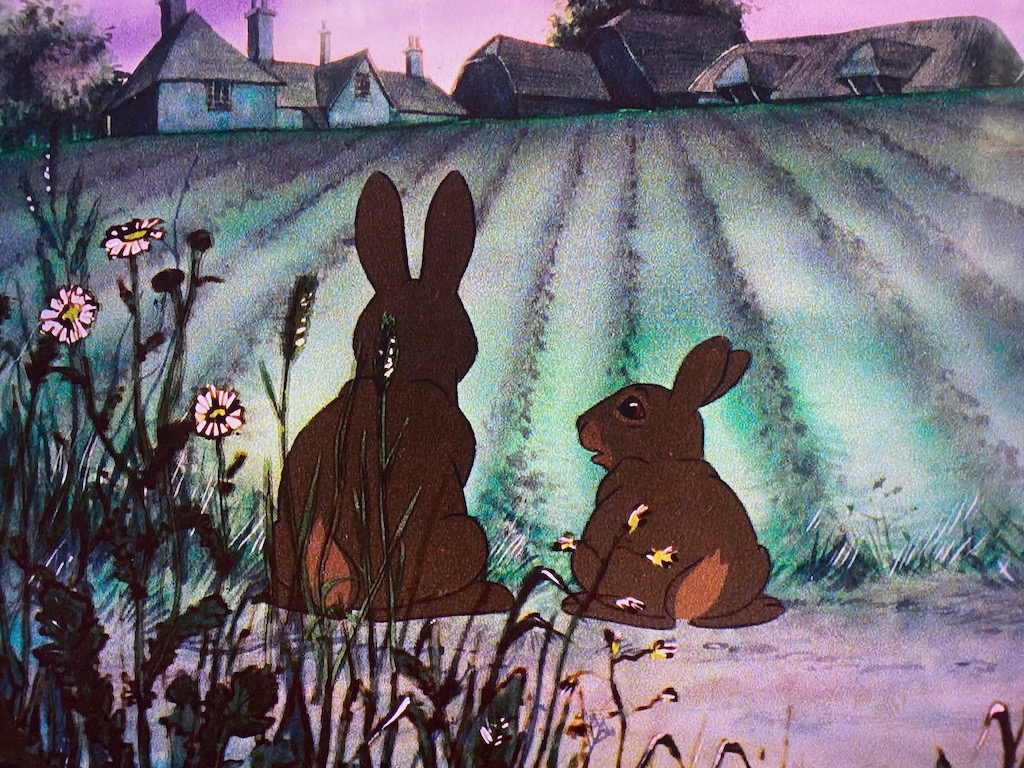

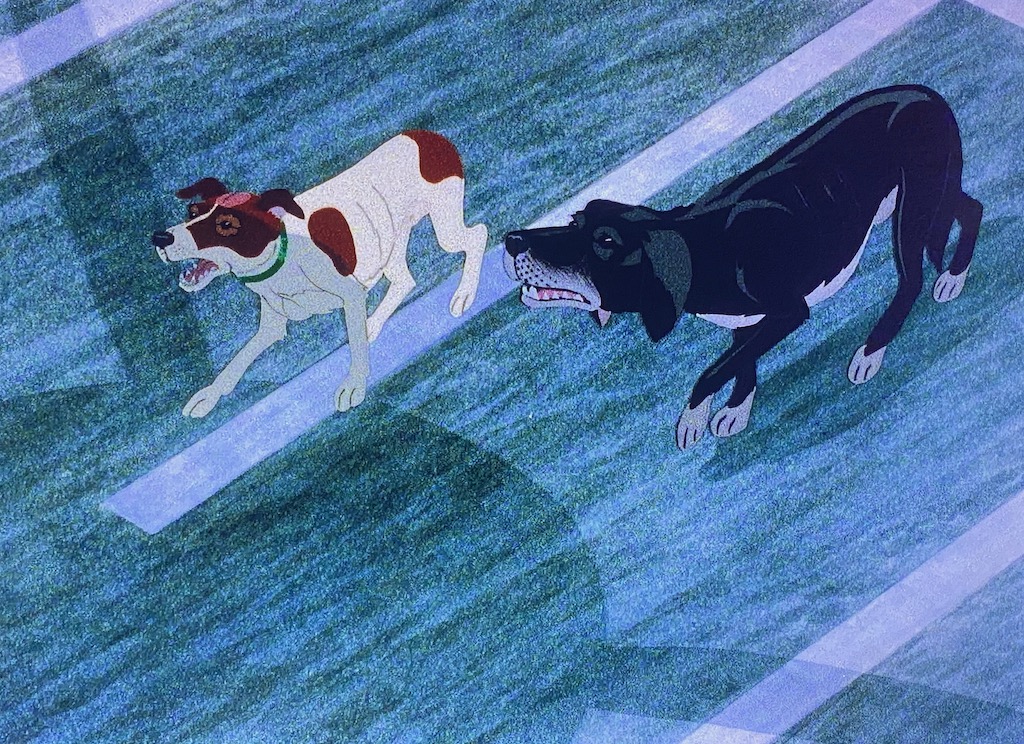

Watership Down and The Plague Dogs explore this same space with unflinching commitment to the animal experience. They are hard, brave, important movies. They don’t look away from the brutality unique to this intersection and how the worst of it results from the influence of humans. Both center animal characters, carefully anthropomorphizing them just enough for we humans to relate, but not enough to fool us into thinking they are anything other than what they are—rabbits, dogs, foxes, birds. It’s a delicate line walked deftly by director Martin Rosen and team in both films.

By author Richard Adams’s own account, Watership Down is a book about rabbits written for children (and not the allegory so many like to school-it-up to be). In both book and movie form, it is a vividly realized tale of courage, peril, loss, survival, adventure, and hope, girded by a rich mythology and fantastic language (which the movie does well not to over-explain).

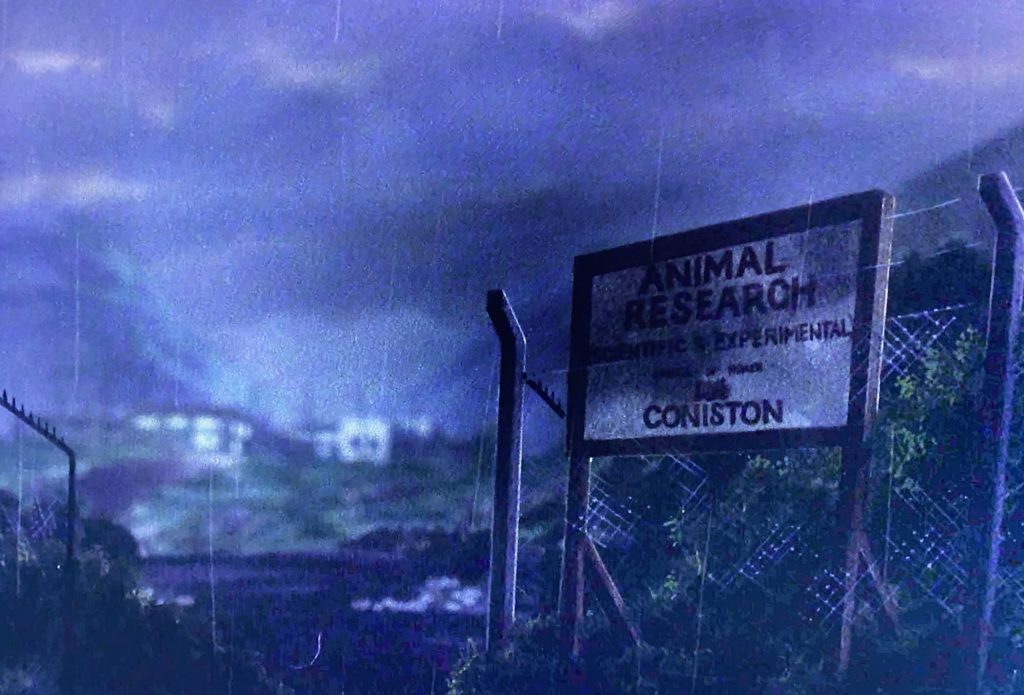

Equally powerful, but leaner and more focused, The Plague Dogs is a different creature altogether. It is an angry story—also based on a book by Adams—fueled by outrage, confusion, and helplessness in the face of the exploitation of animals. A questioning of a world made inhospitable for those that don’t play the role we’ve assigned to them. Here, our canine heroes share screen time with humans, the former giving us more grace than we deserve and the latter displaying more clinical cruelty than most imagine possible.

Many viewers growing up in the age of home video rank the snare strangulation scene in Watership Down among their earliest cinematic traumas, alongside the drowning of Artax in the Swamps of Sadness and the discovery of E.T.’s near-lifeless body discarded on a creekside. The scene, like the act of snaring in the real world (currently legal in 34 states), is violent, long, and horrible to behold. It gets the straight treatment—choking, gasping, flailing, foaming, bloody—without melodrama and is all the more effective for it. Other moments of violence, like Fiver’s initial vision of bloody fields, the psychedelic nightmare developers gassing the warren, and the languorous movements and druggy eyes of the well-kept rabbits, are more stylized, but they give the “real” moments of violence (like the snaring) more emotional heft. So much so that the snaring is what the movie is best known for. This is unfortunate, because the film is gorgeous and moving and engaging and lovingly-made and beautifully acted and, most importantly, makes one feel a deeper empathy with animals than just about anything in the animated universe.

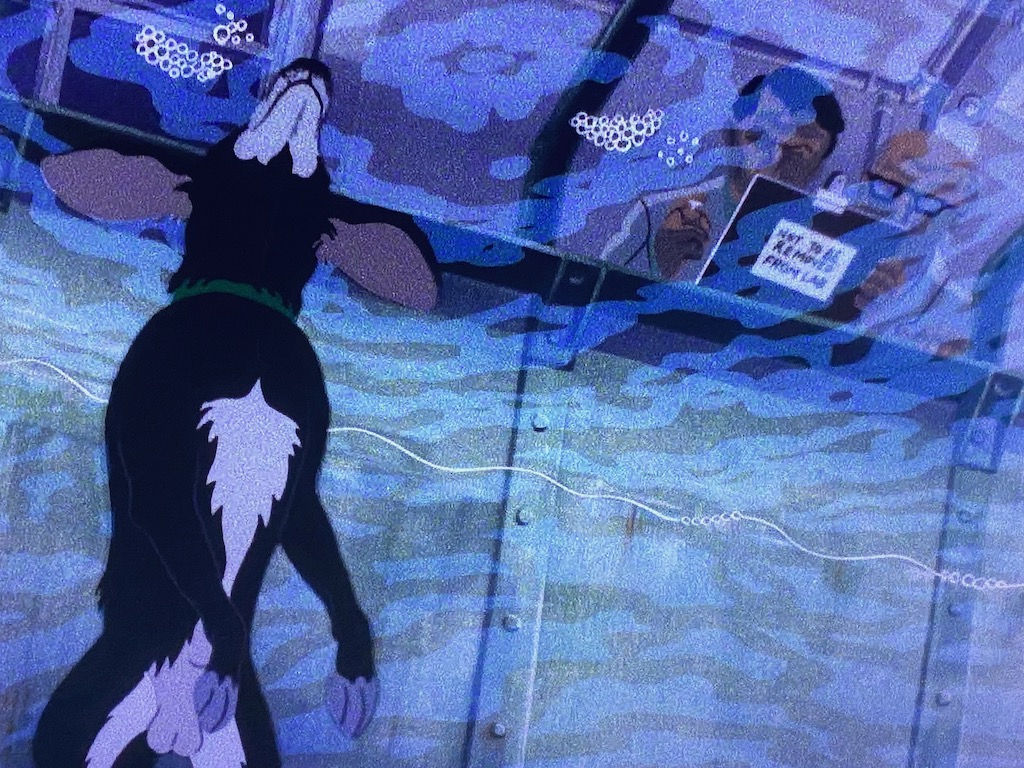

The Plague Dogs doubles down on the reality that inspired it, drawing from accounts of real lab experiments performed on animals to various and questionable ends. It starts with a dog, our hero Rowf, drowning in a metal tank while two scientists stoically take notes and make comments on his progress.

The drowning goes on for ages.

Things get worse from there. It’s no spoiler to tell you there’s no real happy ending—just how Adams originally intended. Rosen stayed true to the author’s vision, which makes for a stronger overall story but resulted in dismal audience reception. With the masses hungry for Watership Down 2, this beautifully bleak bit of cinema was shoveled into the box office incinerator after a brief, dismal initial run. At the premiere, Rosen reported being physically struck by an outraged viewer mid-film, shouting, “How can you do that to those dogs?”[2] That’s exactly the question, I believe, this movie wants us to sit with. To carry home. To not be able to shake. It wants us to consider the animals that live among us, that we allow to live among us, and ask ourselves, How can we? How can we let such things happen? How can we bulldoze ecosystems to build multifamily complexes no one can afford? How can we inject chemicals into rabbits and dogs just to make sure our diet soda is the least carcinogenic in the market? How can we punish animals for our own self-interest, our own greed, our own mistakes? How can we claim to understand them?

These films don’t give us the answers. They also don’t preach. In fact, Rosen tones down Adams’s vitriol significantly, letting the actions of the characters speak for themselves. Simply by virtue of being human we know the score here. We understand our complicity. In watching, the theater becomes an isolation chamber where we have only the beautiful hand-drawn images on the screen, our snacks (with dyes likely tested for safety in rabbits’ eyes) and our “drowning rabbit” memories to keep us company.

The majority of the drama in these films takes place in the overlapping space of the human world, the untamed world, and the domesticated world in terms we are willing to understand: human terms (mostly), in human voices. Because we have such a hard time understanding things in any other way. Watership Down is a story of rabbits fleeing the devastation of human development in search of the wild. The Plague Dogs is a story of escape from scientific abuse into a no-dogs-land where human conditioning (domestication) has made all the world inhospitable. But to leave them at that would be to slap the director and walk out in a huff without getting the point. The heroes of these films move through the world on more than instinct or plot or the divine hand. They are driven by a fundamental desire known by all animals. A desire enjoyed by fewer and fewer of them as we humans push our influence into a disproportionately large share of this world: to live and die on their own terms, no matter the cost.

NOTES

1 The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (Viking, 2015).

2 Shout! Factory DVD special features, 2019.

Edited by Matt Levine

This blog post was worth reading and I learned something. I always presumed that snaring is illegal but now I know otherwise.

The topics of childhood trauma, animal cruelty and how they relate to each other are starting to attract more attention.