| Daniel McCabe |

Watership Down plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, March 24 through Sunday, March 26. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

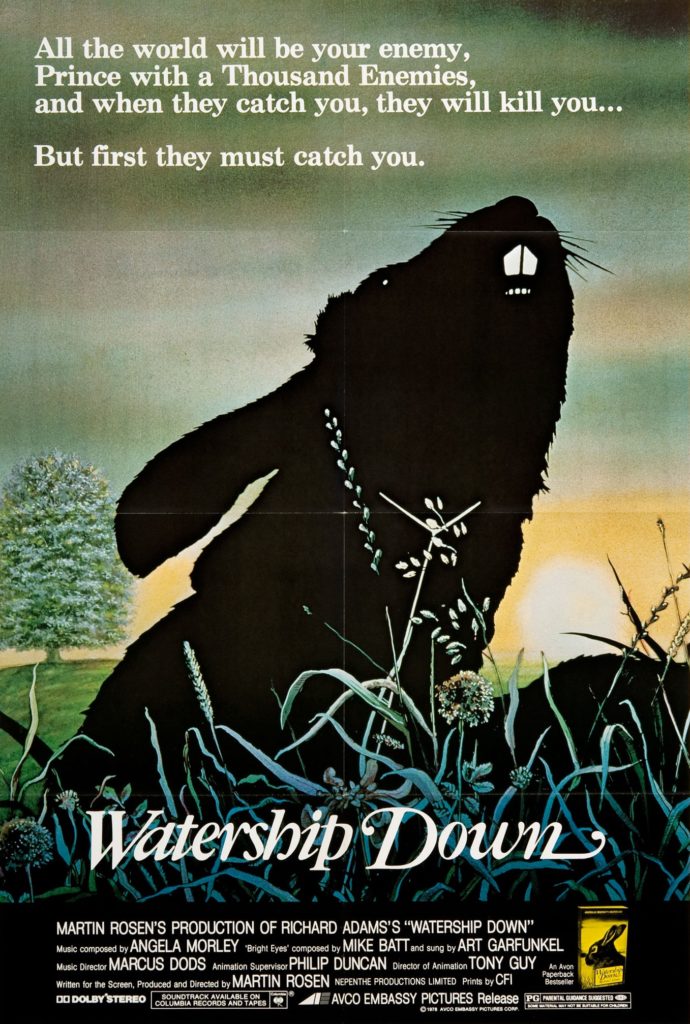

Original US theatrical release poster. Credit: AVCO Embassy Pictures.

Watership Down. The name conjures contrasting images of adorable rabbits and their violent, authoritarian society. Reams of ink and pixels have been expended discussing the film’s timeless plot and emotionally gripping images. It also holds a unique place in the history of animation, released as a pivot point between the decline of the so-called “Golden Age” of animation and the modern era of the artform. While stylistic elements from the Golden Age appear in Watership Down (e.g. hand drawn cells and static backgrounds), it has more in common with the animated films that came after it than those that came before.

The Landscape of Animation in 1978

The theatrical animation industry in 1978 was a shell of its former self. The major Hollywood studios had largely stopped producing animated shorts. MGM released its final Tom and Jerry short to theaters in 1967, and Warner Brothers followed with its final Looney Tunes/Merry Melodies short in 1969. Even Disney, the originator of the animated feature, had scaled back its output considerably by the 1970s. Although the studio still had some successful features, such as Robin Hood (1973) and The Rescuers (1977), it was about to enter a dry spell largely unseen in previous decades. Animation had better luck on television, but with the exception of a few (mostly Hanna-Barbara) shows in the early 1960s, it was relegated to Saturday morning children’s programming slots.

When Cinema International Corporation released Watership Down in 1978, it did so in an environment where animation had nearly run its course as a theatrical art form and had stagnated on television. The film succeeded at the box office, and to this day, it remains one of the most beloved movies in the United Kingdom, but it did not become a global cultural phenomenon in the same way as subsequent animated films of the modern era such as The Little Mermaid (1989), Toy Story (1995), and Spirited Away (2001). That said, Watership Down remains a milestone in the history of animation, heralding a future in which its successors would receive acclaim not just as great animated films, but as great films in general.

Voiceovers Provided by Recognizable Actors

Today, animated films feature some of the biggest stars in the world providing voiceover work. The success of casting big stars in Aladdin (1993), The Lion King (1994), and Toy Story (1995) may have given audiences the expectation of big stars providing the voices of popular characters, but the trend actually began in the 1970s. One of the first notable instances of a famous “movie star” providing a voiceover in an animated feature occurred when Debbie Reynolds provided the voice of Charlotte in Hanna-Barbara’s 1973 adaptation of Charlotte’s Web.

Watership Down took what Hanna-Barbara did by casting Reynolds and upped the ante. Sir John Hurt, one of the most versatile British actors of his generation, provided the voice of the lead character, Hazel-Ra. Richard Briers, a well-known British television and Shakespearean actor, voiced Fiver, the rabbit prophet. In his final film role, Zero Mostel gave life to the bird Kehaar, who helps the rabbits immensely during the film’s climactic scenes. For better or worse, well-known actors providing voiceovers in animated films has become a staple of the medium, and the trend in that direction began in the 1970s with films such as Watership Down.

Realism in Character Modeling

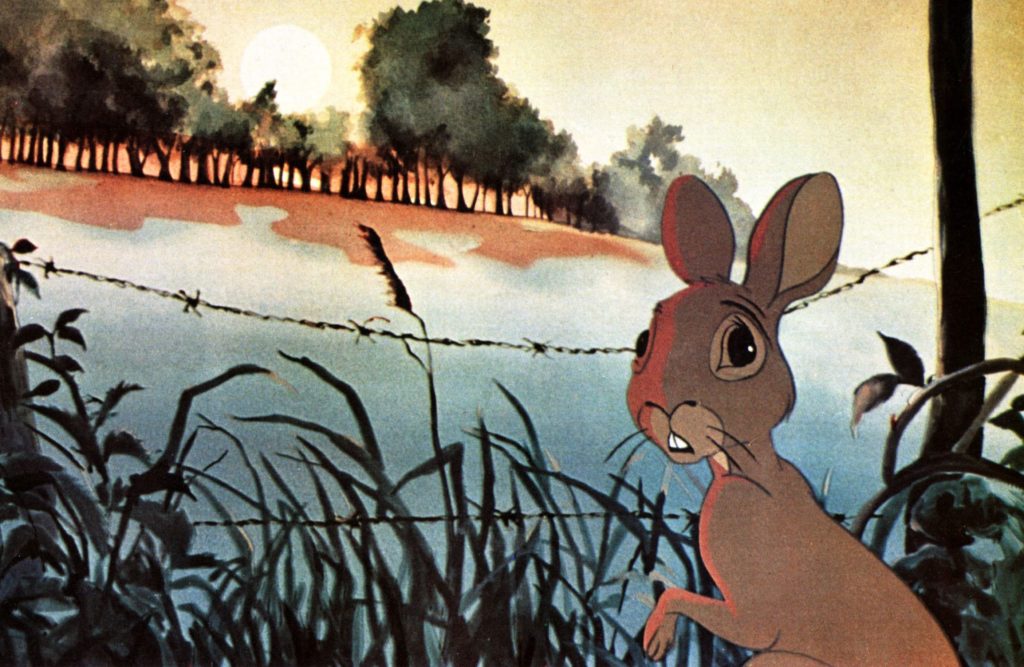

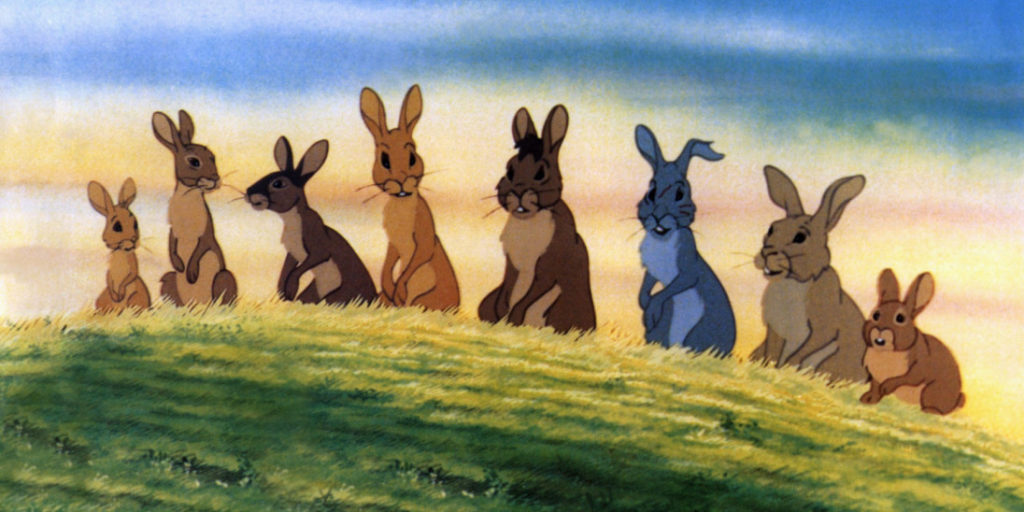

One of the first things that one notices in Watership Down is that the animals aren’t drawn anthropomorphically. The rabbits look like rabbits, without human features such as binocular eyes or expressive mouths. Sure, they talk, but if you compare them to the animals in, say, Cinderella (1950), you can see that Hazel and his friends are not modeled in the “cartoonish” manner common in the Golden Age of animation.

Backdrops in Golden Age shorts and features were often afterthoughts. With few exceptions (Fantasia [1940] comes to mind), backdrops tended to be workmanlike, drawn to fit the scene and little more. In contrast, Watership Down’s creators took great lengths to depict the Hampshire described in Richard Adams’ novel. The result is an immersive experience rarely seen in animation before the influence of anime revolutionized the use of detailed settings and backgrounds in the medium.

Violent Images

Watership Down may feature adorable bunnies, but it is not a story meant for small children. In an era of Pixar and anime films that appeal to both children and adults (or sometimes just adults), this may not seem an unusual statement. However, in the late 1970s, animation had not broken past the “it’s for little kids” label.

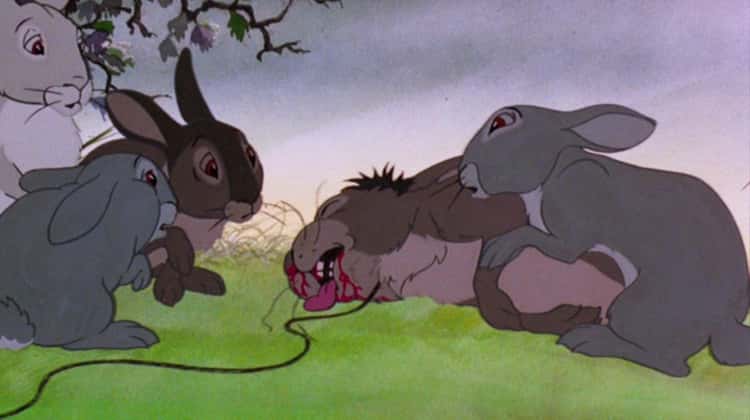

The storyline, involving a group of rabbits fleeing environmental destruction and searching for a home, is not necessarily a complex story for grownups. After all, The Land Before Time (1988) features a similar plot, though it involves adorable baby dinosaurs. No, it is the images, not the plot itself, that create an intensity that may be too much for children of a certain age. Examples include the strain on one rabbit’s face when he’s caught in the trap, or the graphic injuries some of the rabbits sustain during the film’s climax.

Certainly, classic animated films and shorts have their moments of peril. Personally, the scene in Sleeping Beauty (1959) where Maleficent turns into a dragon gave me nightmares as a child. But viewed through the eyes of an adult, that scene from Sleeping Beauty is notable for its lack of visual stakes. In fact, as one of the more useful Disney princes, Philip doesn’t even break a sweat fighting the enormous dragon. Contrast that to the climactic battle between Bigwig and Woundwart in Watership Down, which leaves both rabbits bloodied and exhausted.

A Landmark in Animation

Watership Down was not the first animated film to contain voiceovers from major film stars, include realistically drawn characters, or feature intense visuals. In being one of the first animated films to combine these elements, however, it stands at a crossroads in the history of its medium. Forty-four years later, the development of animation as an art form has grown well beyond its outdated “kids’ stuff” reputation, and early films in the modern era of animation like Watership Down are an important part of that evolution.

Edited by Matt Levine