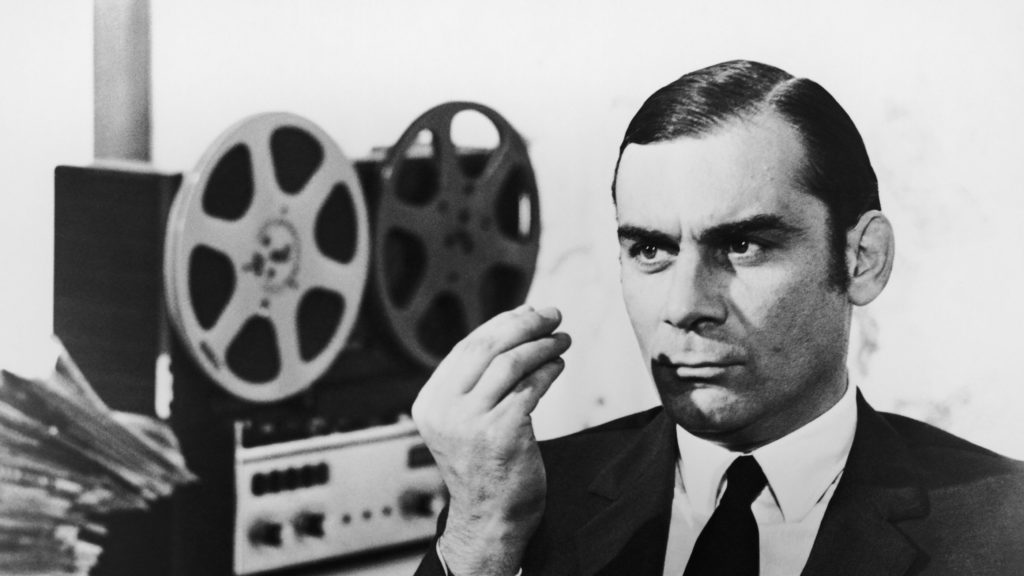

| John Moret |

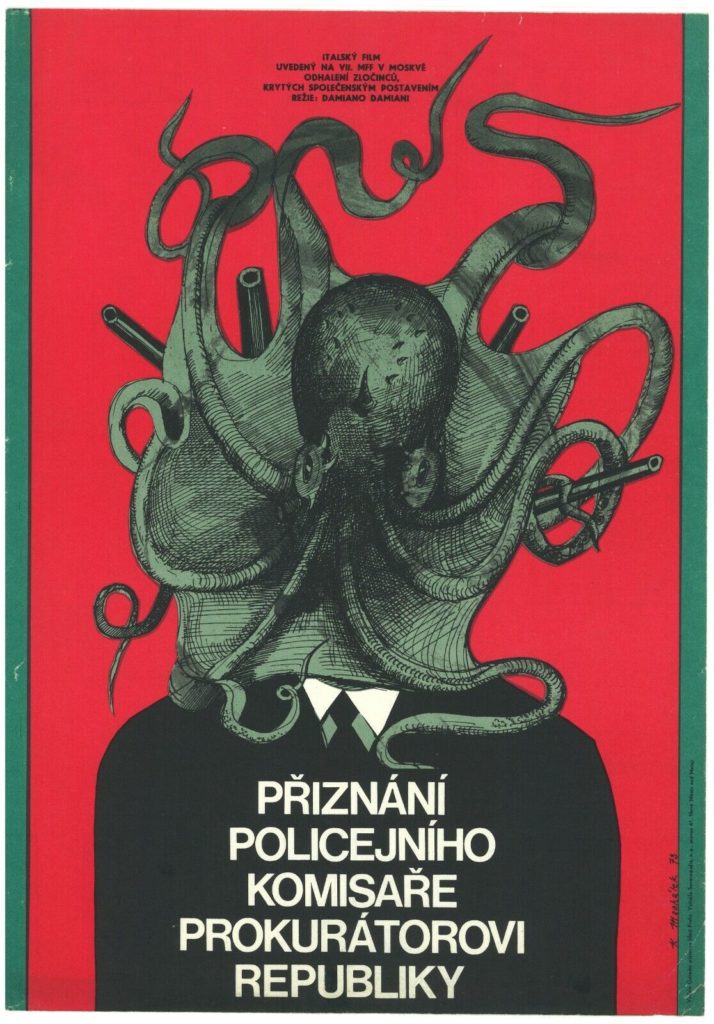

Excerpt from the original Italian poster for Confessions of a Police Captain (1971)

The Poliziotteschi: Italian Crime Films in the Years of Lead series plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, February 5 through Tuesday, February 28. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Generally speaking, I love crime cinema in nearly all its forms. The French Connection (1971), Massacre Gun (1967), The Glass Key (1942), Le Cercle Rouge (1970), Columbo (1971-2003)—pretty much any decade, from any country, you can find genuinely great films that explore the connections between criminals, corruption, and law enforcement.

Eleven years ago (winter 2012), the Trylon did a four-film Fernando di Leo series called Spaghetti Noir. At the time I was volunteering but not yet programming at the theater. I loved the series—particularly The Boss (1973), which features the possibly craziest cold opening ever. I remember it clearly. Get this: Henry Silva becomes aware of a rival mafia gang meeting up in a porn theater. So, Silva does what any excellent enforcer would do—he brings a grenade launcher into the projection booth and blows everyone inside the auditorium to pieces. Yep, that’s the beginning of the movie. The film doesn’t hold its weight after that point, but what a start! The experience of seeing that moment was incredible not only for the grenade launcher, but also because I was one of five people in the audience and after that scene someone blurted out, “damn right!”

The Italian film industry of the 1960s and 70s, more than any other, was about excessive imitation. During that time period there were more than 500 spaghetti westerns, hundreds of gialli, and dozens upon dozens of poliziotteschi films (pronounced Po-Litz-Eo-Tess-Key and meaning “police related”). If a film was successful in the market—i.e., A Fistful of Dollars, The Italian Connection, Twitch of the Death Nerve (aka Bay of Blood)—hundreds of derivative films were sure to follow.

Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970)

On the surface, these Italian crime films may not seem to have the artistry of Fellini and Antonioni, the masterful storytelling and editing in the spaghetti westerns of Leone, or the sheer giallo style of Argento and Fulci. However, with the proper context, we can recognize these crime films as equally important. Some of them (Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion and Confessions of a Police Captain, for example) are better than many of their genre counterparts.

The Italian political landscape of the early 1970s was rife with violence. Assassinations, kidnappings, and car bombs were deployed as neo-fascists and far-rightists battled far-left activists for power. Leftovers from Mussolini’s fascist government still lurked the halls of parliament and on police beats. Detractors and anti-fascists, feeling the powerlessness of the Chamber of Duties (the lower house), resorted to any means necessary to dislodge them. The fascists responded in kind. This infighting led to corruption and tribalism, which spread its tentacles to every corner of Italian society. Policemen could be bought and were ineffective in stopping the soaring crime rate. Authority was untrustworthy. This time period is known as “The Years of Lead.” The poliziotteschi film, then, grew out of a moment somewhat similar to our own. Trust in law enforcement couldn’t be much lower, Washington, D.C. seems to languish in a fascist coup attempt hangover, and our local officials seem entirely helpless to solve the most pressing problems.

I found myself watching a host of poliziotteschi films after discovering Confessions of a Police Captain. The film captures something that I was feeling in the summer of 2020. On a hot night that June, I was returning home from the theater. It was around midnight and the neighborhood around the Trylon and the 3rd Precinct were in turmoil as buildings burned and protestors clashed with the police. I arrived at the intersection of 38th and Hiawatha. The street lights and traffic lights were out, no one was around, and a car burned brightly in the middle of the street. As I slowly drove around the vehicle I found myself gaining a truer understanding of the fragility of our social contract. Over the course of that summer, and the subsequent years, I must have watched 20-30 of these films. I couldn’t put my finger on it, but as I watched film after film I discovered something that linked them together.

Helplessness.

Original 1973 Czechoslovak poster for Confessions of a Police Captain designed by Karel Zlín

These films have been disregarded or criticized for a reliance on violence as a means of solution. I don’t disagree with that take, and there are certainly plenty of these films that are simply mean and irresponsible. However, these four films showing at the Trylon in February hone in on something else going on. These films lean heavily into the dishonorable leaders on one side (Investigation) and the insurmountable odds of correction on the other (Confession). They dig into these themes and offer only cynicism. They seem to say that corruption can only continue with the tacit understanding and inclusion of people, and each day at each moment, leaders make decisions which reinforce or challenge this—and they can’t be trusted to make the tough choices. As a viewer (and citizen), when the wave is crashing down and you feel powerless with no apparent solutions, there is a helplessness that can lead to fantasies of violence as a means to correction. The popular films of our current moment are equally simplistic and fantasy-violence based. It just so happens that the vigilantes of our films wear capes.

In poliziotteschi, there are no superheroes. These films are ugly and messy and have no answers. Perhaps that’s why they’re so intellectually satisfying in the ways they connect to the present state of the world.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon and Matt Levine