| Matt Levine |

Pulse plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, January 6 through Sunday, January 8. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

If two dots get too close, they die, but if they get too far

apart, they’re drawn closer. It’s a miniature model of our

world. I wouldn’t suggest staring at it too long.

Harue Karasawa (Koyuki), discussing a computer program in Pulse

We become what we behold. We shape our tools and then

our tools shape us.

Father John Culkin, SJ1

The turn of the millennium occasioned many films that lamented and/or celebrated the digitization of the world as we knew it. The Matrix and its sequels envisioned all of humanity living in a virtual reality while machines sucked out our lifeblood, turning us into nothing more than consumable energy sources. eXistenZ (1999) offered a Cronenbergian spin on the distortive nature of virtual reality and its ability to erase the boundaries between real and imaginary. The Net and Hackers (both 1995) showed how fragile security and privacy are when you live your life online. Films like Enemy of the State (1998), A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), and Minority Report (2002) offered warped depictions of digital technology overriding all aspects of society, from law and order to the nuclear family. Sometimes, the aesthetic itself was digital, with movies like Timecode (2000) and All About Lily Chou-Chou (2001) presented in proudly pixilated formats. In short, Y2K-era cinema was obsessed with digital ubiquity, prophesying how our lives, minds, and bodies might change as we become increasingly “logged on.”

Among this group of films stands Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse, which has the distinction of being one of the scariest and most philosophical horror movies of all time. Bearing Kurosawa’s elegant but intensely creepy slow-burn style, which brought pervasive dread and unease to films such as Cure (1997) and Séance (2001), Pulse is a ghost story in which the phantoms of loneliness and alienation are (almost) as terrifying as the literal specters that appear onscreen.

Anyone who tried to log onto the internet in the 1990s will recognize the first sound that we hear in Pulse: a dial-up modem from the days of AOL, screeching as it tries to connect to cosmic satellites. But this sound jarringly cuts to an image in which digital technologies seem conspicuously absent: a cargo ship in the middle of the ocean, surrounded by an endless expanse of water. Only gradually will we learn the apocalyptic context of this image, as the film soon flashes back to its dual storylines.

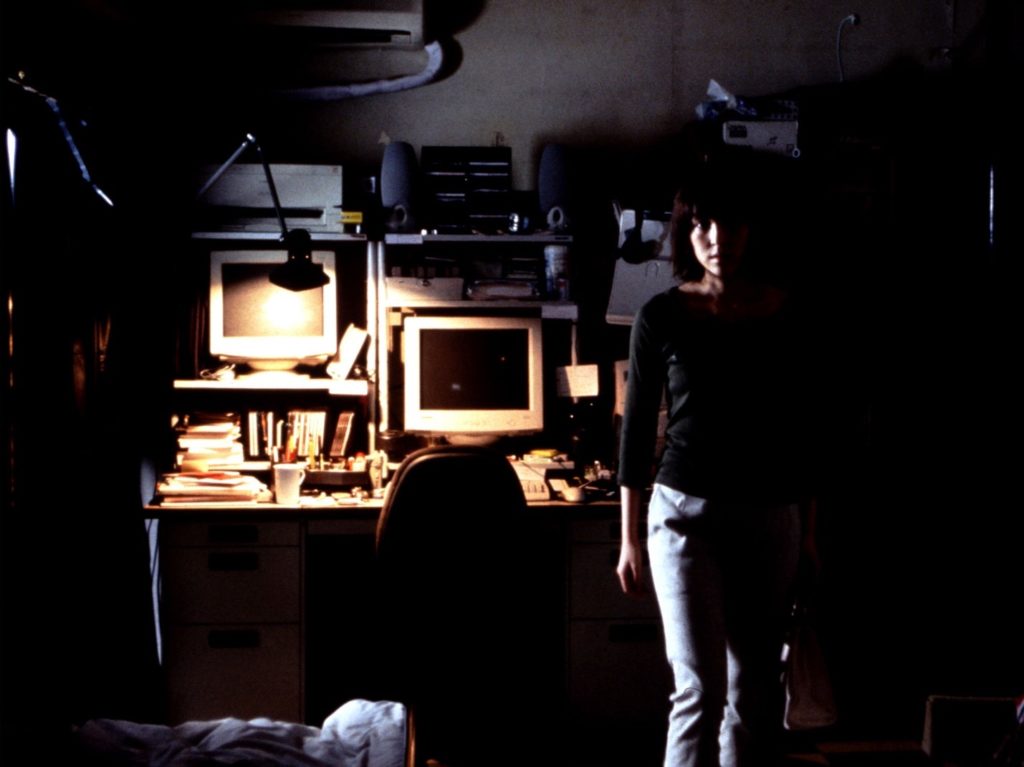

One of these storylines begins with a young man named Taguchi (Kenji Mizuhashi) trying to restore a computer disk for the plant shop at which he works. Taguchi’s apartment, like many of the interior spaces in the film, is cramped, dark, and foreboding. Kurosawa brilliantly instills a sinister presence through visual form, first of all through disorienting POV shots that make us unsure if the images are from a detached, omnipotent perspective or if we’re seeing through the eyes of…something. The very first image in this flashback is an unnerving example: we witness the empty apartment, half of the screen obscured by a plastic sheet, through a brown-gold haze as the image glitches and distorts every few seconds, accompanied by a digital screech similar to the modem sound at the beginning. As soon as we enter Taguchi’s apartment, the film suggests that we’re sharing a perspective with a disembodied, digital presence, observing everything with eerie detachment.

Kurosawa also rattles the audience through subtly menacing camera movements, which we witness when one of Taguchi’s coworkers, Michi (Kumiko Asō), visits his apartment to check on him after he’s been missing for a week. Her journey to Taguchi’s apartment is conveyed through a jarring, blatantly unreal rear-projected image in which Michi is seen on a bus with passing scenery visible through the windows; the scenery is a different color scheme than the bus interior and the movements of the vehicle and the surroundings don’t match up. This tactic is used several times throughout the film, with vehicles and rear-projected images clearly belonging to separate spaces, illustrating a world that’s becoming increasingly unmoored from its physical places—a product, it seems, of the digital ether surrounding it.

Once Michi finally reaches Taguchi’s apartment, she examines his computer and workstation, finding the disk from the plant shop; the camera tracks away from her and pans to the left, revealing a narrow hallway again obscured by a plastic sheet. This camera movement, which abandons Michi for no discernible reason, sets us up to expect a sinister threat lurking in the shadows, but instead Michi occupies the frame once more, moving through it. This is one small example of how Kurosawa moves the camera not only to progress the narrative, but to establish a pervasively ominous tone, nudging the audience to see things that aren’t really there (or are they?).

This is a good time to reiterate: Pulse is absolutely terrifying, with Kurosawa brilliantly manipulating sound design, camera angle, and cutting to torment the audience. The horror here isn’t just jump scares and violence; it’s a lingering dread that burrows deep within, made all the more chilling by its inexplicability. Case in point: a scene in which Yabe, after searching for clues in Taguchi’s now-haunted apartment, enters a “Forbidden Room” sealed in red tape, encountering one of the most unshakeable ghosts you’ll see in all of cinema. (This moment, which I won’t ruin here, is proof that there’s nothing scarier than staring headlong into the face of evil, unable to turn away.)

While Michi, Yabe, and their coworkers try to figure out what happened to Taguchi, a parallel storyline ensues. A shy, awkward economics student named Ryosuke (Haruhiko Kato) logs onto the internet despite the fact that he hates computers, which is conveyed when he dubiously opens his browser’s instructional manual and mumbles aloud: “Welcome to the internet. Have fun.” Almost immediately, his computer misbehaves, treating Ryosuke to eerie images of people in separate rooms, recorded on grainy screencams: a man looking vaguely toward the screen; a woman rolling on the floor, her movements lagging; a man burying his head in his arms; a woman walking from right to left. Then, a popup message: “Would you like to meet a ghost?”

Ryosuke’s computer keeps behaving unpredictably, logging onto the internet of its own volition and showing a horrifying image of a man strapped to a chair with a bag over his head, with messages reading “Help me” scrawled on the walls behind him. Understandably shaken, he visits the computer science department at a nearby university and meets a grad student named Harue (Koyuki). She’s the one who utters the epigraph at the beginning of this review, describing a program that one of her cohorts created which shows white, fuzzy dots gravitating near each other but never touching—a “miniature model of our world” in which people constantly crave companionship but can never truly attain it, in her view. “People don’t really connect, you know,” she says somberly. “We all live totally separately.”

Harue’s character is fascinating, and in some ways acts as the skeleton key to unlocking Pulse’s meaning. She briefly describes her morbid childhood: “I always wondered what it was like to die from when I was really little. I was always alone. But then it dawned on me…after death you might be all alone too.” One wonders if her preoccupation with death and loneliness inspired her to study computer science, or if her interest in that field bestowed an obsession with connecting (or not) with other people. The film itself seems to agree with her viewpoint that every soul, whether living or dead, perpetually (and fruitlessly) craves the company of another. She confirms this when she turns on a series of monitors, each of which shows a hazy image of someone planted at their computer, invariably alone. “How are they different from ghosts?” she asks (in dialogue admittedly a bit too literal). “In fact, ghosts and people are the same, whether they’re dead or alive.”

Another grad student, Yoshizaki (Shinji Takeda), explains to Ryosuke what the audience has already surmised: our living world has started to become overrun by ghosts who use digital devices and technologies as portals into our reality. The realm of dead souls has finite capacity, Yoshizaki explains, and “once that realm reached critical mass, any device would have sufficed” to allow them access to our own world. As Yoshizaki offers his hypothesis, we see a dreamlike origin story in which a room at a construction site has its internet port ripped from the walls, apparently giving rise to this ghostly infestation. As the dead overlap with the living, people begin vanishing into thin air, leaving behind black scorch marks as the only traces of their former existence. Even the software program that Harue shows Ryosuke begins acting erratically, with the fuzzy white dots glitching more violently and swallowing up others.

Eventually the two storylines converge in a shockingly apocalyptic finale, as nearly the entire world falls prey to lonely phantoms who possess the living. The uniquely 21st-century dystopia in which Pulse culminates is of the melancholy sort: a logical endpoint for digital ghosts and human beings who find eternal companionship in some kind of limbo, neither living nor dead. All of this is best viewed metaphorically instead of literally; it’s not always clear how the “Forbidden Rooms” materialized, with their ominous red tape, or exactly what kind of connection these ghosts have with the living. But Pulse’s emphasis on atmosphere over logic is far from a weakness: this is impressionistic horror at its most primal, offering a poetic depiction of a nascent 21st century soon to be subsumed by isolation.

How could such foreshadowing be deemed anything but prophetic? The COVID era of social distancing, in which most of us communicated, worked, bought supplies, and entertained ourselves largely through the internet, is only the most blatant example of separate lives taking place on a linked-in network. The communities formed online and the selves fashioned on social media may be attempts to forge togetherness, but the end result is often fragmentary and disharmonious—all of us little fuzzy dots coming close to each other, but never actually touching. Pulse’s proclamations of despair and alienation can seem overstated, but they’re hard to deny as our lives play out in the digital realm more fully with each passing year. (The fact that Michi and her colleagues work at a plant shop is no coincidence: that’s one of the only signs of the natural world that we see in Pulse, a stark contrast to the otherwise thoroughly modern environs.)

As John Culkin writes in the other epigraph above, the technologies we create bear the impressions of our fears, desires, insecurities, and longings. Before we know it, those very technologies deepen the human emotions that shaped them in the first place, exacerbating what they were meant to alleviate. If the internet arose out of our desire for communication and synchronicity, it has often served the exact opposite purpose, allowing us to exist in discrete worlds which amplify the things that separate us.

A number of films dramatize this phenomenon (including some of those listed in the intro), but Pulse’s brilliance lies in its use of the horror genre to present this theme. The internet can be a scary place—a warning expressed figuratively by Pulse’s shambling ghosts, pale, unblinking faces, and disembodied voices. There’s tremendous philosophical insight in the film, but, maybe more importantly, there’s a nightmarish visual power that encapsulates the brink of the 21st century in ways that don’t always make sense. It remains unclear how exactly these ghosts enter our world and possess the living, but to witness their lifeless, unblinking faces return our stare and plead for help is to understand something new and dreadful about our (dis)connected existence. After watching Pulse, the wifi-enabled device in your pocket will seem more threatening than ever before.

NOTES

1 Father John Culkin, SJ, “A Schoolman’s Guide to Marshall McLuhan,” Academic, March 1967.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon