| Chris Polley |

Catch Nic Cage films all summer at the Trylon. For more information, visit our website at trylon.org.

“Tomorrow you will die. Nicolas Cage.”[1] This is one of the earliest recountings of the Hollywood staple’s autograph signings, as told by Raising Arizona co-star Sam McMurray to Insider for an oral history of the film. McMurray witnessed Cage commit these words to a cocktail napkin for a young woman while out to lunch during the shoot of the 1987 comedy classic, and honestly, I can’t think of a signature that better suits the cinematic icon.

Now, like many teenage boys in middle school in the mid-late 90s, I wasn’t privy to this self-aware and anarchic mode of Cage. In fact, I was under the impression that his cartoonishness was accidental rather than manufactured. My developing mind saw his performances in Michael Bay’s The Rock and Simon West’s Con Air as only a few degrees removed from, say, Steven Seagal in Under Siege, when in fact what he was up to was something more akin to, oh, say, Eric Bogosian in Under Siege 2: Dark Territory.

I didn’t figure this out fully until 2002, as I started learning about film academically at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities, when I witnessed his dual meta-portrayal of screenwriting twins Charlie and Donald Kaufman in Spike Jonze’s Adaptation. And this is around the time when I started to dig back into Cage’s filmography, anxious to see what other rules of sincerity and irony, charisma and caricature that he had not-so-secretly been breaking. A whole world of zany opened up to me: from the mainstream mania of Martha Coolidge’s Valley Girl to the warm chaos of David Lynch’s Wild at Heart, and yes, eventually, the Coen Brothers’ Raising Arizona.

It helped that this personal journey through Cage’s filmography in the early 2000s coincided with another, arguably even more fruitful laundry list: that of the filmmaking duo of Joel and Ethan Coen. O Brother, Where Art Thou? showed how funny and still empathetic bumbling criminals can be, so I was excited when I learned the conceit of Raising Arizona and immediately moved it to the top of my Netflix DVD queue (physical media nostalgia alert). I still remember letting the breakneck pre-credits opening sequence wash over me for the first time in my dorm room and getting giddy for what was to come.

As Chris Nashawaty summarizes this tour de force in storytelling and editing for Esquire, “We see boy meet girl, boy flirt with girl, boy console girl, boy propose to girl, boy marry girl, boy stare down disappointment with girl, boy console girl again, and finally, boy plan a felony with girl that will walk us up to the subsequent 83 minutes of the film.”[2] And as many others have pointed out over the years (including elaborate fan art), from the extravagant costuming to the exaggerated angles, before you even see some of the film’s most iconic shots, it’s clear we’re in for essentially a Tex Avery-style live-action cartoon.

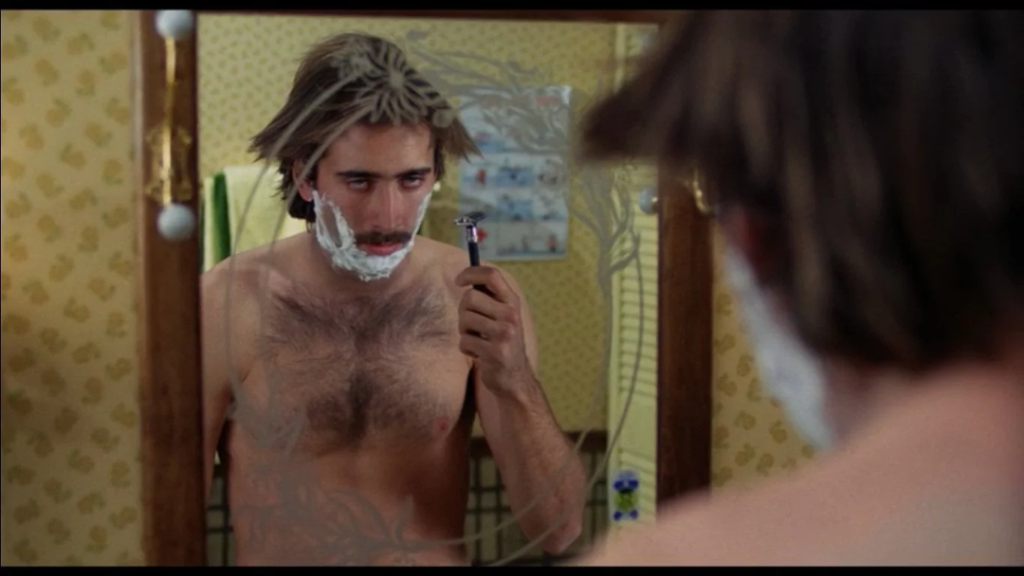

I’d go even further to argue that this very apt observation’s central puzzle piece, which without it would not be nearly as universally noted or celebrated, is the man in the middle of it all—Nicolas Cage. Nephew to Francis Ford Coppola, and thus an inarguable nepotism case, he proved early on in his career that he is one of those rare exceptions to the rule that having a family connection in Hollywood invites mediocrity to the artform. Love him or hate him, his presence is magnetic here, and even the most hardened viewer that remembers the pre-memeification of Cage; anyone who hears his deadpan drawl during the opening narration and witnesses his glorious mustache and magnificent coif should be able to appreciate a rising actor in his utmost element.

Steven Hyden describes the indelible performance for Uproxx as “comic and lovely, outrageous and affecting, unreal and authentic—all of the things you love about Nicolas Cage and rarely get all in one place.”[3] In this character, we truly do get everything we’ve ever asked of the thespian, and I’d be curious to hear from some true old heads that were privy to the rise of the Coens and Cage what it was like to see his turn from something so perfectly suited for his sensibilities (along with his manic yet comparably minor turn in Moonstruck, which arrived the same year as Raising Arizona) to his boisterous mainstream action-flick, box-office success in the mid–late 90s.

Yet there are even hints at that persona ever present throughout the caper’s brisk 94-minute runtime. Comical explosions, inane character choices, and absurd chase scenes populate H.I.’s central attempt at staying out of jail and kidnapping a child in order to start a family with his barren wife Edwina (also admirably played with equal parts empathy and lunacy by the masterful Holly Hunter), which are honestly not that far removed from some of the foolishness that fills modern trash classics like Knowing, Ghost Rider, or Next. One of those is even literally a comic book adaptation and another is from the director known for his graphic novel adaptations!

Now, what exactly makes Cage the one best suited for this kind of unhinged job, compared to, say, other possible creatively emotive leading men of the time period such as Mickey Rourke, Kurt Russell, Al Pacino, or—another actor that would, a decade later, make another of the Coens’ most iconic protagonists—Jeff Bridges? As Chris Coffel for Film School Rejects observes, “Cage is like a jazz musician, relying on improv to guide him through a set until he finds a groove he likes [whereas] Ethan and Joel [are] much more meticulous with their approach. When they arrive on the set they know what they want to shoot and that’s what they shoot.”[4]

While there may be a case for a version of the film with Bridges (there’s a reason John Goodman is also here, hamming it up like he always does best with the Coens in a memorable—if rather diversionary—supporting role), what stands out to me about Cage in this role ultimately boils down to one specific moment in the film’s closing moments (so, spoiler alert if you’re into that kind of thing): when the victim of the kidnapping, Nathan Arizona (played by Trey Wilson, succeeding at somehow making the audience feel pity and scorn), asks H.I. and Ed why they brought the baby back.

“In a reward situation, they usually say ‘no questions asked,’” H.I. responds. With this small, existential non-answer that the Coens have been so famous for since Blood Simple, Cage nails a combination of sadness and acceptance, of ingeniousness and empty-headedness, that he proves the role and the film isn’t as easily boiled down to “live-action cartoon” as a surface-level reading may find. He takes the role of ex-con kidnapper in a flamboyant tropical shirt that just wants to be a good dad and a better husband deadly seriously, and thus finds the truth in his character’s internal duality—how desire and death are intrinsically linked, how a tiger can’t change its stripes but is still alive and striving, so it can only (winking emoji) stay Caged for so long.

NOTES

[1] Gregory James Wakeman, “An oral history of ‘Raising Arizona,’ the comedy classic that made Nicolas Cage a star,” Insider, March 16, 2022, https://www.insider.com/raising-arizona-behind-the-scenes-stories-nicolas-cage-35th-anniversary-2022-3.

[2] Chris Nashawaty, “The First 11 Minutes of Raising Arizona Are the Best Opening To Any Movie Ever Made,” Esquire, April 29, 2022, https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/movies/a36287882/why-raising-arizona-has-the-best-opening-scene-of-any-movie/.

[3] Steven Hyden, “The Pinnacle: Why The Best Nicolas Cage Performance Is In ‘Raising Arizona’,” Uproxx, August 31, 2017, https://uproxx.com/movies/nicolas-cage-raising-arizona-medium/.

[4] Chris Coffel, “The Tao of Nicolas Cage: ‘Raising Arizona’,” Film School Rejects, April 21, 2017, https://filmschoolrejects.com/tao-of-nicolas-cage-raising-arizona-5695e979f0ad/

Edited by Michelle Baroody