| Nick Kouhi |

I Know Where I’m Going! screens at the Trylon from Friday, January 21 to Sunday, January 23. For tickets and more information, scroll to the bottom of this screen.

Throughout the nearly twenty films they made together through their production company, The Archers, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s heroes and villains tell stories to each other and themselves that elicit meaning from the psychologically entrenched yearnings governing their lives. Joan Webster (Wendy Hiller), the heroine of their winsome fairy tale romance I Know Where I’m Going! (1945), is no exception. Made at the end of the Second World War, the film situates its industrious, middle-class English woman within a Scotland which is affectionately, if ethnographically, transformed into an amalgam of disappearing indigenous customs and influences from other, multinational fables.

For Powell, Scotland was a site of Edenic fascination, its rolling hills and seaside cliffs previously rendered in mythic monochrome for his 1937 feature The Edge of the World. Powell’s return to the Scottish Highlands with Pressburger shifted further away from realism to heighten the mystical topography of the Hebrides. I Know Where I’m Going! (IKWIG!)[1], anticipates the theistic dimensions of their succeeding feature, A Matter of Life and Death (1946), with wry wit in its opening credits of an omniscient narrator guiding us through the first quarter-century of Joan’s life in less than two minutes of screen time. With diegetic props featuring the names of the film’s cast and crew, the contrast of a male narrator recounting an ambitious girl’s growth into womanhood playfully signals a conflict which is both distinctly gendered and more broadly existential.

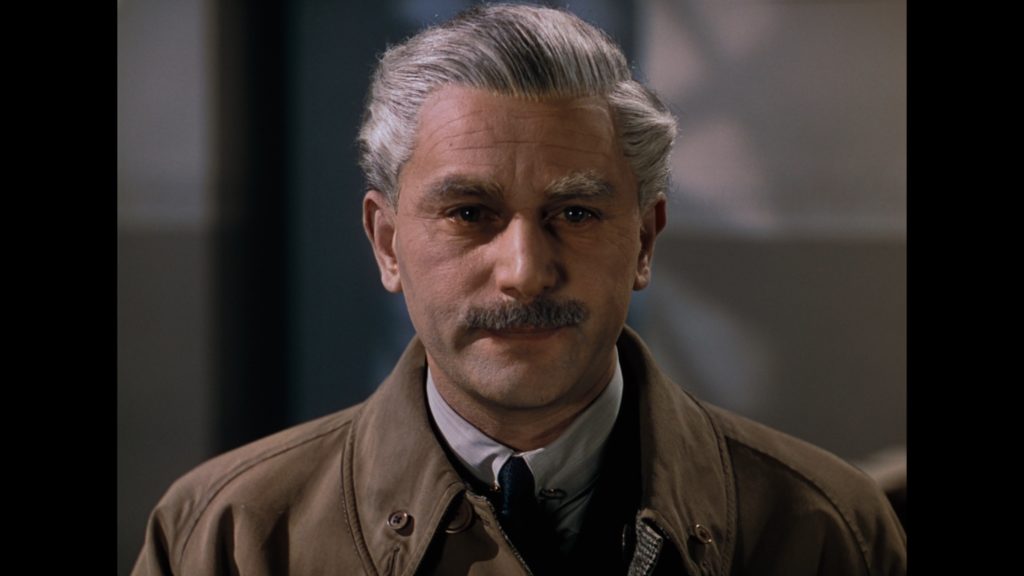

Another conflict, one between modernity and tradition, characterizes the Archers movies made during WWII. In IKWIG!, the specter of combat is relegated to the occasional reference, like the remarks by Torquil MacNeil (Roger Livesey), the Scottish naval officer on his eight-day shore leave. Torquil acts as Joan’s guide while she waits for safe passage to the (fictitious) island of Kiloran. Her fiancée, the wealthy industrialist Sir Robert Bellinger, awaits her on the island he rents from the impecunious Laird, who is none other than Torquil himself. Joan’s plans inevitably dovetail as her adventures draw her and Torquil closer together.

Scottish indigeneity is most celebrated (and exoticized) in the film’s centerpiece, a cèilidh commemorating the diamond anniversary of two of the community’s oldest members. Taking from his firsthand account of a cèilidh he attended, Alexander Carmichael describes it as a forum “where stories and tales, poems and ballads, are rehearsed and recited, and songs are sung, conundrums are put, proverbs are quoted, and many other literary matters are related and discussed.”[2]

The music recited in the cèilidh set piece was arranged by Scottish actor John Laurie, a member of the Archers’ stock company who appears in IKWIG! as the son of the couple marking their anniversary. The songs in this scene are significant for both the film’s narrative and thematic thrust. When Torquil translates the lyrics of Ho ro My Nut Brown Maiden from Gaelic to English, ostensibly making clear his romantic affections for Joan, the intrusion of a musical narrative on Powell and Pressburger’s veneer of rustic naturalism is emphasized by the diegetic sound of bagpipes swelling to a crescendo in the background. While this dramatic revelation is most important for the plot, Powell & Pressburger emphasize another, seemingly incidental musical moment in this sequence; a performance of a melancholic tune sung a cappella by the partygoers, filmed in a long tracking shot. Much like the vanishing island community of Hirta in The Edge of the World, the Scottish traditions in IKWIG! are, as Pam Cook writes, “consigned to the past and retrievable only through memory.”[3] Significant to this is how, time and again, Powell and Pressburger conjoin memory and storytelling in their fabulist cinema.

These twinning strands abound in Col. Blimp, most poignantly in a sequence where Wynne-Candy’s former nemesis turned lifelong friend, German soldier Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff (Anton Walbrook), recounts to British customs officers the loss of his family and country to Nazism. In a long take, the camera dollies slowly in on Theo’s face as he verbally sketches an image of his late British wife’s country envisioned while he was on the outskirts of Berlin. Wes Anderson emulates this homesickness in his paean to storytelling, The French Dispatch of the Liberty Kansas Evening Sun, when Lt. Nescaffier (Stephen Park) summarizes the loneliness of being an immigrant in a foreign country with the maxim, “Seeking something missing. Missing something left behind.” Cook argues the multinational composition of The Archers (Pressburger, for instance, was a Hungarian Jew who fled the Nazis) complements the contemporary diaspora of Scots from their homeland to the United States during the war. In that respect, it’s tempting to read IKWIG!’s Scotland as occupying the liminal and deeply personalized space between “fiction and reality”[4], much in the way the Himalayas do in The Archers’ adaptation of Black Narcissus (1947).[5]

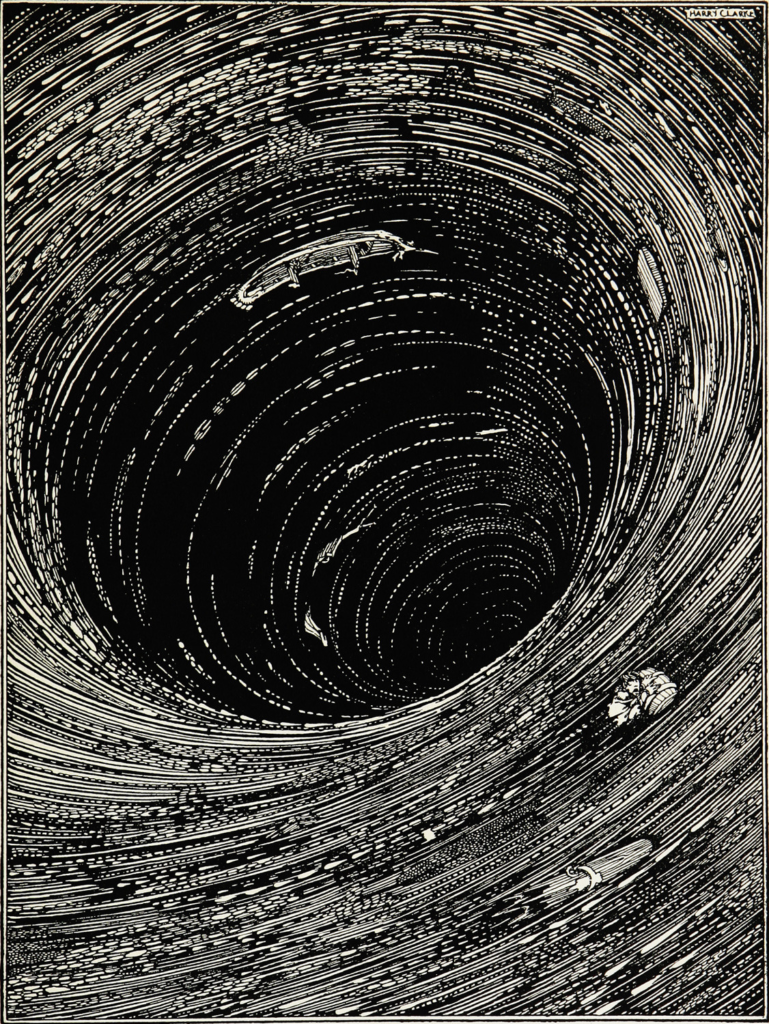

The latter’s dynamic between civilization and nature is emblematized in IKWIG!’s spectacular climax where Joan’s mounting desperation to reach Kiloran leads her, Torquil, and a young man (Murdo Morrison) into the maw of the Corryvreckan whirlpool. The tale of Breacan, a Norse prince who drowned due to his beloved’s disloyalty, gives this fusion of on-location footage and special effects its name. Yet the sequence was also influenced by one of Powell’s favorite short stories, Edgar Allan Poe’s A Descent into the Maelström.[6] In it, the lone survivor of a shipwreck recounts to an anonymous listener how he escaped the titular whirlpool, his encounter with death moving from feelings of fear to awe. With these influences in mind, I would argue that the lauded climax of IKWIG! remains gripping because, like Poe, Powell and Pressburger understand the function of narrative in helping us make sense of, and ultimately confront, our impending mortality, all in the context of a Europe itself finally emerging from the maelstrom of war.

Another narrative of love conquering brutal death guides the film’s closing passage when Torquil crosses the threshold of Castle Moy under threat of a curse put upon his family name by the MacLaine clan. The curse, influenced by Sir Walter Scott’s reliable use of the trope[7], resolves the violent retribution Torquil’s ancestor enacted on his (un)true love by leaving him “chained to a woman”, propitiously signaled by Joan’s triumphant return. Yet Joan choosing Torquil once he’s fulfilled the matriarchal curse is riven with ambivalence. Marie-Alix Thouaille argues that Torquil’s “deliberate[…] triggering [of] the curse in a desperate bid to reclaim Joan before she crosses to Kiloran” ultimately privileges a heteropatriarchal conservatism.[8] “Taming a woman must be worse than taming an eagle,” Torquil muses to his falconer friend, Colonel Barnstaple (Captain C.W.R. Knight) evoking Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. While Joan remains a compelling heroine, her taming by Torquil does little to challenge Thouaille’s argument that her love interest ultimately works to “exercise control over [her] mobility,” containing her like Petruchio contains Katherina.[9]

Social anxieties over the role of upwardly mobile women in Britain are filtered through an anti-materialist attitude borne out of wartime scarcity. Despite his assurance to Joan that “You’re all right as you are,” Torquil’s transformation is comparatively slight compared weighed against Joan’s rejection of the “soulless empowerment” of consumerist affluence.[10] Throughout The Archers’ corpus, the gulf between men and women is acknowledged with ironic melancholy, as in Col. Blimp when Wynne-Candy attempts to remake the image of his unrequited love into two nearly identical redheads (all played by Deborah Kerr). Yet it is most often the women who are humiliated into admitting their mistakes (as in IKWIG! or Black Narcissus) or, at worst, destroyed, even when their paternalistic destroyers are targets of criticism by Powell and Pressburger.

These critiques don’t necessarily nullify the proto feminist elements of I Know Where I’m Going!, yet I do suggest we take heed of the slippery nature of storytelling here and in the rest of the Powell and Pressburger canon. We can still view Wendy Hiller as the co-author of Joan Webster without ignoring the regressive attitudes which informed her character, or celebrate the cosmopolitanism of The Archers even as we examine their progressive limitations. This bewitching, often propulsive feat of imaginative filmmaking shows us how the finest of fables can help us discover where we’re going by showing us, for good and ill, where we’ve been.

[1] This acronym has been used previously by Pam Cook and Marie-Alix Thouaille, among others.

[2] Alexander Carmichael, Carmina Gadelica, Volume 1: Hymns and Incantations, 1900, https://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/cg1/cg1002.htm

[3] Pam Cook, I Know Where I’m Going (London: BFI Classics, 2021), 70

[4] Ibid., 49.

[5] For more on the depictions of India and Scotland in these films, see David Hanley’s “Strangers in Strange Lands: Encountering the Exotic in I Know Where I’m Going and Black Narcissus,” January 19, 2012, https://offscreen.com/view/strangers_in_strange_lands#:~:text=Gunning%2C%20Tom.,Ian%20Christie%20and%20Andrew%20Moor.

[6] Michael Powell, A Life in Movies: An Autobiography (New York, NY: Knopf, 1987), 465

[7] Powell, A Life in Movies, 468

[8] Marie-Alix Thouaille, “‘Intelligent Female Nonsense’: Pastoral, National Identity, and Shakespearean Misrule in A Canterbury Tale (1944) and I Know Where I’m Going! (1945),” eSharp, no. 23 (2015): 14, https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_404378_smxx.pdf

[9] Thouaille, “‘Intelligent Female Nonsense,'” 14.

[10] Ibid., 12.

Edited by Brad Stiffler