| Matt Levine |

Husbands screens on 35mm at the Trylon from Sunday, September 19 to Tuesday, September 21. For tickets and more information, scroll to the bottom of this page.

Husbands zeroes in on the real state of love and sex in our time… Cassavetes, Gazzara, et al., I salute you as fellow liberationists.

–Betty Friedan, 1971 [1]

The brutality with which women are often treated in Husbands––which the film’s bullying macho ambience often seems to endorse (or at least tolerate) more than criticize––turned me against Cassavetes for a number of years, and I still haven’t resolved whether this description of the film qualifies as a misreading.

–Jonathan Rosenbaum, 1991 [2]

For those who view art primarily as a way to monitor political correctness, Husbands is something of an impossible film to deal with. Is it misogynist or feminist? A celebration of belligerent, abusive men or a vicious condemnation of them? Should one align their perspective with Betty Friedan, who organized the Women’s Strike for Equality only two months before Husbands premiered in 1970 and applauded its attack on toxic masculinity? Or with Jonathan Rosenbaum, one of the most influential critics of the latter twentieth century, who was rightfully put off by the film’s insistence on detailing the ways its central characters berate, humiliate, use, and ignore the women in their lives? The answer, of course, says more about each individual viewer than it does about those two cultural commentators, or even about the film in question.

John Cassavetes didn’t make movies to get on a soapbox or wring his hands over moral dilemmas. From his directorial debut, Shadows (1958), to at least Love Streams (1984)—if you discount his last directorial effort, Big Trouble (1986), as he did himself—he made films about the messiness of human existence. They were rough and abrasive for that very reason, but also vital and sometimes overwhelmingly powerful. As the godfather of American independent cinema, he made it clear that his characters were not heroes or villains but an exasperating in-between, and political questions of racism, misogyny, or class were not debates to be won but lived experiences to be portrayed with an unflinching eye.

Husbands is, in many ways, Cassavetes’ most extreme film, revealing to us repugnant people with an almost stubborn, unwavering commitment. Even more extreme than the characters’ awfulness, though, is the sense of empathy the film still manages to evoke on their behalf. Yes, they’re detestable—lonely, desperate, loud, abusive, obnoxious, insecure drunks—but we see something painfully human in their mutually-destructive friendships, and we relate to their existential terror at the realization that life, at a certain point, holds no more surprises.

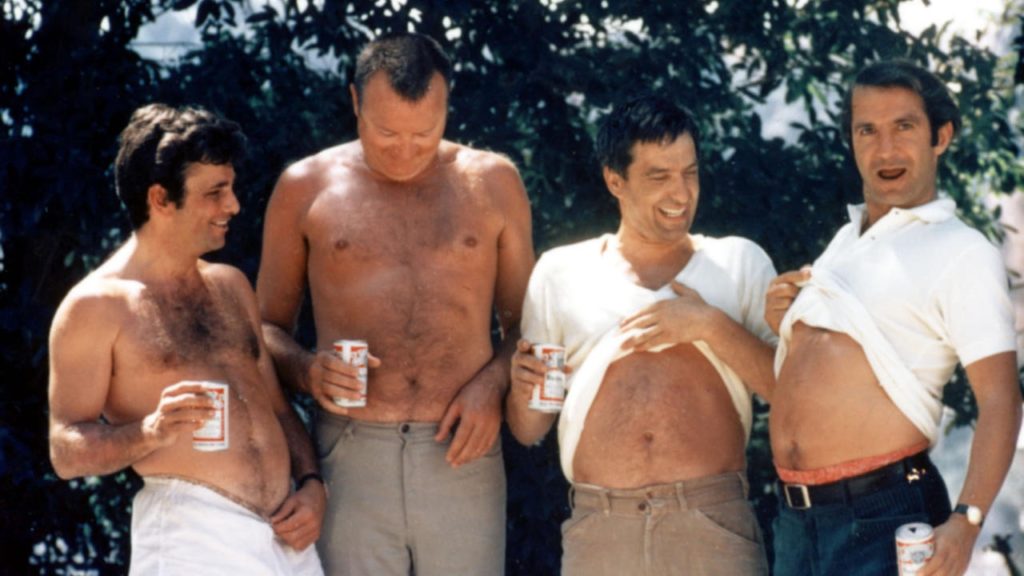

The film starts with a series of still photographs, family snapshots of husbands and wives and children lazing around a pool. The “husbands” in these images are four close friends—Gus (Cassavetes), Archie (Peter Falk), Harry (Ben Gazzara), and Stuart (David Rowlands)—and we get a sense of their boorish personalities even from these photographs: they flex their pathetic muscles, play-wrestle at the side of the pool, beer cans perpetually in hand, their wives lingering in the background. We see Gena Rowlands, Cassavetes’ real-life wife, in this early montage, her only appearance in the movie; already, Cassavetes indicates how personal the story is meant to be, a ruthless autobiography that one hopes is wildly exaggerated.

The next scene is a funeral—Stuart has died. Even though he was only middle-aged, Stuart’s heart gave out, perhaps because of all the copious drinking. All the black shiny cars and pomp and circumstance “seem pretty dopey for a guy like that,” says Archie. Harry, ushering Stuart’s elderly mom toward the gravesite further ahead, looks back at them jealously—the characters’ personalities, alike on the surface but disastrously unique deep down, are suggested within the first four minutes. “Lies and tensions, that’ll kill you,” Archie tells a perplexed Gus—not smoking or alcohol, he insists, but the lies and tensions of modern life.

Archie’s apologia is not convincing, and his critique of the overlong eulogy at the funeral feels equally insincere (“Say he died too young and that’s all, that’s it”). The artificiality of this early dialogue seems intentional (though the performances were decried as stilted when the movie first came out); these men are terrified at this reminder of their own impending mortality and they focus on anything else to distract themselves. As we’ll come to see, they feel suffocated by their nine-to-five jobs and nuclear families—the very things they were told to aspire to in American life—and claw frantically to break out of them.

Now seems like an appropriate time to emphasize what the film will tell us over and over again: these are not admirable characters. Husbands may provide contexts for their repulsive behavior, but it doesn’t make excuses for them or blame society. If these men are paralyzed by the responsibilities of family and capitalism, that’s largely a result of their own cowardice and insecurity. Any compassion the opening scenes of Husbands engender is immediately offset by a shot of Gus, Harry, and Archie drunkenly singing at the top of their lungs on a city sidewalk—a scene of privileged vulgarity with which we’ll soon become familiar. “We can do anything we want to do,” Archie says on the subway moments later. “So what do you want to do?”

The answer: wrestle each other on busy sidewalks (nearly running over passersby) and play basketball (poorly) at the gym. Afterwards, the men embark on a marathon of binge drinking and casual cruelty. At a dimly lit bar, in a scene that goes on for twelve minutes, they insult each other, force a poor woman to sing and then ridicule her performance, take off their clothes, and chug beer with increasing abandon. The next scene, which lasts nine minutes, shows them vomiting in a narrow bathroom and fighting with each other over absolutely nothing. These back-to-back scenes perfectly encapsulate the movie’s grim audacity: it is a naked portrayal of toxic masculinity at its most destructive.

Shouldn’t a movie about toxic masculinity be hard to watch? Husbands was and is attacked for its long wallow in disgusting male behavior, but it’s very clearly about the ways in which misogyny spreads unabated. Expecting a movie about the violence of patriarchy to be timid and pleasant is absurd at its core. The anger and sadness of a movie like Husbands seems appropriate since it deals with the forces of sexism that have given rise to the Harvey Weinsteins, Andrew Cuomos, Brock Turners, Brett Kavanaughs, Jeffrey Epsteins, et al. of the world.

And yet—Husbands is a film with sudden sparks of humor and bizarreness. Gus, a dentist, treats a patient who’s high on nitrous oxide and steals the scene in which she appears. Harry, an ad man, sits forlornly in his office (a photo of his kids prominent in a striking diopter shot) before one of his colleagues points, giggles, and greets him in a maniacal falsetto. Once the men flippantly decide to jet off to London—having the money and privilege to escape their lives at the drop of a hat—Archie is hit on by a dolled-up socialite with the weirdest line readings one can possibly imagine (delivered by a marvelous Delores Delmar). Even a tragic farewell between Gus and Archie at the end is made absurd when they flippantly exchange toys to give to their kids, negotiating who will be the deliverer of which stuffed animal.

Cassavetes’ label as a gritty realist has never been totally accurate; he’s in love with the process of acting, the spontaneity of the scene, the strangeness of life. His surrealistic tendency is most explicitly presented in Love Streams’ ending, which I won’t ruin here though it involves a stoic dog and a naked old man. Cassavetes’ weakest film, Opening Night, is enlivened by a late scene in which Gena Rowlands hijacks a live theatre performance by forcing Cassavetes into increasingly strange improvisations. (Indeed, Opening Night is a case study in the somewhat irrelevant question of whether or not Cassavetes is a feminist—the film simultaneously presents Rowland’s character, Myrtle, as a victim of showbiz patriarchy and as a hysterical fantasist who can’t control her own life.) The caustic honesty of Husbands is made bearable by the film’s (bleak) sense of humor and its unexpected oddities.

That said, Husbands remains unflinching throughout. After the men’s opening bender, Harry returns home to discover his wife intends to leave him with her mother (who lives in the same house) in tow. Harry forcibly kisses his wife, pushes her down on her knees, and chokes and slaps both her and her mother. Afterwards, Gus and Archie console him in the front yard, bemused but hardly repulsed by his behavior. (This scene has a lot in common with similar moments in Elaine May’s Mikey & Nicky [1976], which also stars Cassavetes and Falk as emotionally fragile men who mask their vulnerability with a show of macho violence.) Later, in London, the men try to cheat on their wives with women they pick up at a casino, mostly unsuccessfully; they pretend to be lotharios but are afflicted by their own psychological hang-ups. “My wife used to do that for me,” Harry says as his new lover, Pearl (Jenny Lee Wright), gives him a massage in a hotel room.

Gus, Harry, and Archie pretend for a while that they can live forever in England, completely abandoning their lives and families, but there is no escape. They return to Long Island despondent, a fate like Stuart’s inevitably awaiting them, with little chance for excitement (aside from the narcotic sort) in their future. It all culminates in Gus and Archie’s return to their modest middle-class homes. The final scene is heartbreaking, the clearest indication in the film of how patriarchy spreads from adults to younger generations; the fact that Gus’s kids are played by Cassavetes’ real-life children, Nick and Xan—the latter of whom breaks down in inexplicable tears upon her father’s return—reiterates how painfully personal the film is. Gus’s kids know full well—as children always do in fractured homes—how cruel and inattentive their father is.

I cringe as I write this, but it’s still true: Husbands is devastating because it’s relatable. I hope and I think that my friends and I are nothing like Gus, Harry, and Archie. But I’ve seen this behavior, and I’ve often recoiled from it but said nothing. I’ve seen friends and loved ones drink in a desperate bid to escape the doubts and miseries of their own lives. I’ve seen men who believe that getting drunk is an excuse to use women for their own fleeting satisfaction. I’ve seen people get drunk and insult, demean, and fight others, including the ones closest to them, their innermost aggressions coming out with the aid of endless alcohol. I’ve felt shame the day after I’ve witnessed or enabled behaviors close to what the men in this movie do. I’d be willing to bet most of us have. It’s one of Husbands’ greatest and most disturbing feats that it makes us relive that shame all over again.

Husbands’ raw emotional brutality remains difficult to watch, but it also feels more urgent and necessary than ever. The forces of patriarchy that permeate American life have hardly abated over the last fifty years. Men like Gus, Harry, and Archie continue to hold positions of privilege no matter how cruel and destructive they are. And while large-scale crimes of misogyny—like those committed by Weinstein or Woody Allen or Bill Cosby—have been rightfully condemned, countless smaller instances of patriarchal violence continue to fester, unreported and largely unpunished.

Given the high stakes of Husbands’ subject matter, the film’s vicious and unrestrained tone is something like a caustic balm. The modern state of American independent movies is timid and lackluster for many reasons, but one of them is a hyperaware political correctness—the fear of being labeled sexist or racist or offensive in any way. That’s why ostentatious message movies like Promising Young Woman and Green Book feel the need to utter obvious moral judgments that don’t have much to do with real life; in the process, they demonstrate little sympathy for the lived experiences that victims of sexism or racism actually undergo. Just like Hollywood movies after the rise of the Hays Code in the 1930s felt the need to explicitly punish characters who transgressed their ethical rules, modern American movies are pressured to portray people as noble heroes or rotten villains, dismissing the fact that every human being is a vexing middle ground between the two. In a culture that’s quick to condemn, the ambiguity of human nature is an uncomfortable fact that most movies and other works of art would prefer to sidestep.

Husbands exists squarely in that ambiguous middle ground, which is why it’s so sad and infuriating. The characters here aren’t heroes or villains, victims or perpetrators, but everything at once. Recently, Donald Glover made headlines for claiming (via Twitter), “We’re getting boring stuff and not even experimental mistakes (?) because people are afraid of getting cancelled.” It’s hard to disagree. While cancel culture enables powerful ways for exploited communities to expose the actions of their oppressors, it can also lead to an atmosphere of creative timidity in which depiction of repugnant behavior is mistaken for endorsement.

Cassavetes can be criticized for many things, but timidity is not one of them. Just as feminism in the 1970s was, perhaps, more radical and empowering than it is now, so too was American cinema unafraid to be militant and provocative. Husbands is a perfect (if unlikely) representation of both. So here’s to more movies that are as unpleasant, difficult, raw, and uncompromising as this one. What we see onscreen is disgusting and infuriating. Why don’t some of us feel a similar kind of outrage when we witness such things in real life?

NOTES

[1] Betty Friedan, “Unmasking the Rage in the American Dream House,” New York Times, January 31, 1971. https://www.nytimes.com/1971/01/31/archives/unmasking-the-rage-in-the-american-dream-house-the-american-dream.html

[2] Jonathan Rosenbaum, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991) 160.

Edited by Brad Stiffler and Michelle Baroody